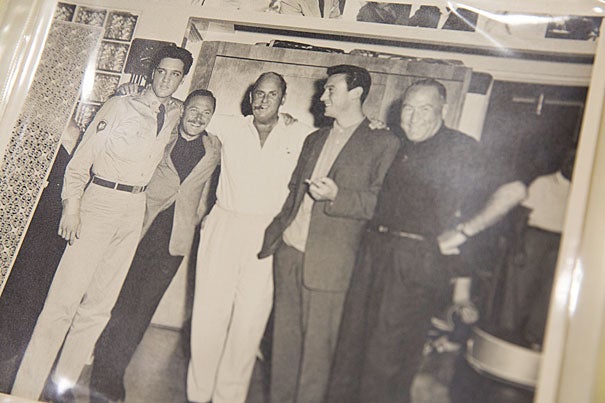

Tennessee Williams (second from left, photo 1) poses with Elvis Presley on the set of the movie “GI Blues” in 1960. The picture is part the Harvard Theatre Collection’s Tennessee Williams Papers at Houghton Library. “It’s an important collection that reveals much about the playwright’s life and his working process,” said Houghton reference librarian Micah Hoggatt (photo 2), who has helped numerous scholars search the trove of material over the past several years. Susan Pyzynski (photo 3), Houghton’s associate librarian for technical services, recently discussed the Harvard Theatre Collection’s Tennessee Williams Papers.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Encounters with Tennessee Williams

National Book Award finalist among the projects helped by Harvard’s holdings

He was a troubled soul whose inner turmoil often played out in the trials of his characters. At Harvard, revelations from the life of Tennessee Williams (1911-1983), one of America’s most celebrated playwrights, can be found in a comprehensive collection of manuscripts and ephemera at Houghton Library.

The nearly 24 linear feet of material in the Harvard Theatre Collection’s Tennessee Williams Papers includes drafts of plays, correspondence, diaries, photographs, and other documents that deliver tender and occasionally tragic glimpses into the work and life of the artist who shot to fame after the Broadway premiere of his family drama “The Glass Menagerie” in 1945.

“It’s an important collection that reveals much about the playwright’s life and his working process,” said Houghton reference librarian Micah Hoggatt. “Because there’s not a critical edition of his productions, really being able to go back to primary sources is critical for researchers.”

Tennessee at Harvard

The Harvard Theatre Collection’s Tennessee Williams Papers at Houghton Library include early family photos such as this shot. Williams is seated in the chair at left. From his right is his nurse, Ozzie, his mother Edwina, sister Rose, and grandmother Grand. Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

An early childhood picture of the playwright Tennessee Williams. On the left is a photo of his sister Rose.

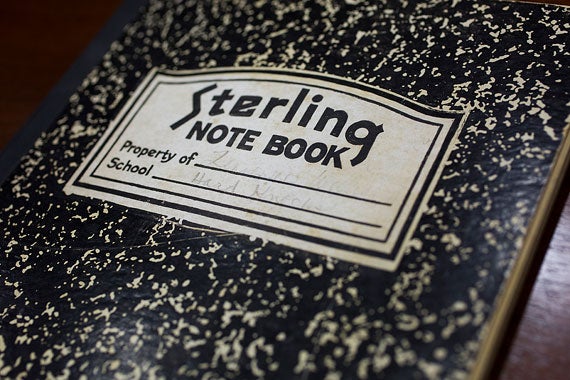

A personal journal kept by Tennessee Williams is part of Houghton Library’s holdings. Next to the world school on the journal’s cover, Williams wrote “hard knocks.”

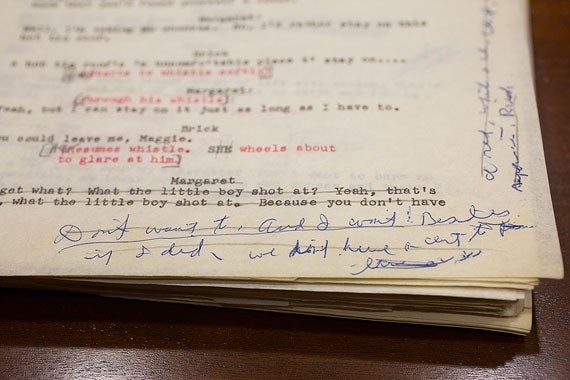

A 1962 promptbook, the copy of the stage script edited for publication in book form, for Williams’ Pulitzer Prize-winning play “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.” At the bottom of one page Williams continued to tinker with dialogue for the play’s hardened protagonist Maggie.

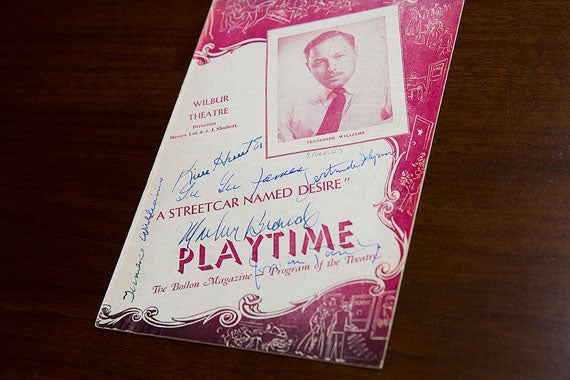

A playbill for the 1947 run of Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire” at Boston’s Wilbur Theatre includes autographs from Marlon Brando, Jessica Tandy, and Tennessee Williams along the side.

A death mask for playwright Tennessee Williams is included in the Harvard collection.

Among the material is a 1962 promptbook, the copy of the stage script edited for publication in book form, for Williams’ Pulitzer Prize-winning “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.” At the bottom of one page, scrawled notes in blue pencil reveal how Williams continued to tinker with dialogue for Maggie, the play’s hardened protagonist.

“We can see he’s actually still working on it here,” said Hoggatt. “He’s taking out lines.”

Other items speak to the author’s demons. Williams struggled with depression, his sexuality, alcohol, and, later in life, with his failing fame and career.

A black-and-white photograph snapped days before the Broadway opening of “Menagerie” captures his discomfort at a small dinner party. In contrast, just a few seats away, Laurette Taylor, who would go on to give a command performance as the play’s faded Southern Belle and overbearing mother Amanda Wingfield, demands the table’s attention.

“This is right before he becomes the great playwright,” said Susan Pyzynski, an associate librarian for technical services. “You can tell she is holding court, and he is so nervous … he often had this anxious look about him.”

Similarly, a page from Williams’ journal written in March of 1943 includes the lines, “I am dull, but I go on writing. Yes, alarmingly dull, a wet match maybe won’t strike anymore.”

The bulk of Harvard’s collection came in 1988 by way of Williams’ literary executor, Maria St. Just. “She convinced him that it should come to Harvard because she was concerned that his work should continue to be thought of in esteem,” said Hoggatt. “She thought that Harvard’s reputation would help in that regard.”

One person who has made use of the material is John Lahr, theater critic for The New Yorker. The author relied on the collection while working on “Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh,” a finalist in Wednesday’s National Book Awards.

“I hope what this does is put a new lens on the glasses of the reader,” said Lahr of his 604-page biography, which was initially envisioned as a sequel to Lyle Leverich’s 1995 chronicle of Williams’ early life and career. But Lahr’s book works as a stand-alone narrative. “Lahr’s research soon transformed the proposed sequel into a grander account of an extraordinary and in many ways unfulfilled life,” according to recent review in The Guardian.

Some of that research took place during a busy day in 2009, when Lahr and a research assistant explored the collection looking for what the author called “thematic things,” behavioral things that had to with Williams’ “hysteria” — the force that Lahr says dominated the playwright’s life. Much of that hysteria was tied to Williams’ turbulent family life.

Particularly revealing was a piece of correspondence between Williams and his collaborator and friend, the director Elia Kazan. The letter, Lahr writes in his book, illuminates the “lethal, castrating dimension” of the playwright’s overbearing mother, Edwina Dakin Williams.

Just after her death in 1980, Williams wrote to Kazan: “Only four feet eleven, she conquered my father who was six feet and drove him out of the house as soon as she received half of ‘Menagerie.’ Allowed the state hospital to perform one of the earliest lobotomies on Rose [the playwright’s sister]. Unconsciously managed to turn both her sons gay.”

Since 2004 the library has received requests from 65 individuals for 426 items from the Williams holdings. And usage has steadily increased. Ten years ago there were between 10 and 20 requests. In 2013 there were close to 100.

“Because of restrictions that had been placed on publication by his literary estate, it’s really only within the last 15 or 20 years that Williams, arguably the greatest playwright of his generation, has received the scholarly attention you would expect,” said Hoggatt. “His letters and notebooks have been collected and edited in that time, which in turn has caused greater interest in his work and brought more researchers to the library. It’s exciting to see the scholarly reflection on Williams begin to take root and grow through projects that really couldn’t have occurred without consultation of our collection.”