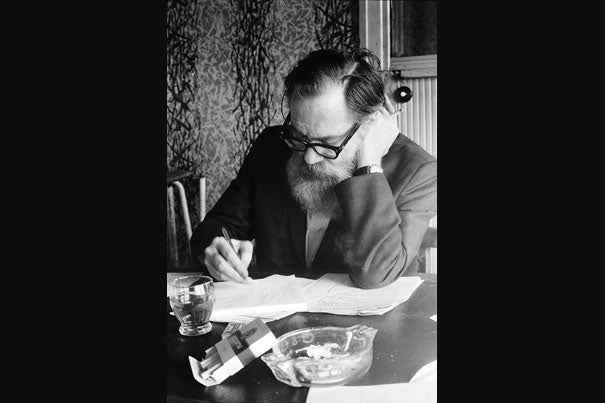

Oct. 25 marked the centennial of the poet John Berryman, who was Harvard’s Briggs-Copeland Lecturer on English from 1940 to 1943. Berryman jumped from the Washington Avenue Bridge in Minneapolis in 1972 at the age of 57.

Terrence Spencer/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

‘Dream Songs’ and demons

John Berryman centennial reintroduces Pulitzer-winning poet and onetime Harvard lecturer

“Nobody is ever missing,” concludes “Dream Song 29,” one of the many anxious, unruly, and death-addled verses by John Berryman.

The poet himself has been missing since Jan. 7, 1972, when he jumped to his death from the Washington Avenue Bridge in Minneapolis. Berryman, a Harvard lecturer from 1940 to 1943, was 57. This month his longtime publisher, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, is marking his 100th birthday by reissuing some of his best-known work.

Suicide haunted Berryman from the get-go. Born John Allyn Smith Jr. in 1914 in McAlester, Okla., he relocated to Tampa, Fla., with his father John, a banker, and mother Martha, a teacher. When Berryman was 12, his father shot himself, and his death, and the subject of death, infuses the poems. In his Pulitzer Prize-winning “77 Dream Songs,” published in 1964, Berryman wrote:

—If life is a handkerchief sandwich,

in a modesty of death I join my father

who dared so long agone leave me.

A bullet on a concrete stoop

close by a smothering southern sea

spreadeagled on an island, by my knee.

Berryman took a new last name when his mother remarried, and the family moved again, this time to New York, where he studied at Columbia, graduating in 1936. At Harvard he was the Briggs-Copeland Lecturer on English and published his first volume, “Poems” (1942).

Berryman was teaching at the University of Minnesota at the time of his death. He’d been fired from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop for a fight with his landlord that led to his arrest. He was, without a doubt, a rabble-rouser. He was also an alcoholic, a manic-depressive, and an adulterer whose odd, tragic, and droll poems engaged with his demons. Those poems live on today, according to poet and Professor of English Stephen Burt.

“He was eclipsed during the 1980s because he’s so individual, and so unreliable as a commentator on anything except for his own inner life,” said Burt. “But his combination of torment and playfulness; his intense awareness of literary tradition; his bizarre rhymes; his ability to respond with verbal extremes to absolutely anything; his way with a character who is himself and not himself; his humor — these aspects of the ‘Dream Songs’ in particular made him a great resource for American poets of the 1990s and afterwards … He’s a resource still.”

Reading Berryman is a roller-coaster ride. His tragicomic poems electrify, confuse, startle. In the “Dream Songs” Berryman employs multiple personalities: Henry, a recalcitrant galoot, and his sidekick, commentator, and foil, Mr. Bones.

In “Dream Song 4,” Henry’s desire is palpable, if a little creepy:

Filling her compact & delicious body

with chicken paprika, she glanced at me

twice.

Fainting with interest, I hungered back

and only the fact of her husband & four other people

kept me from springing on her

“It’s hard to read ‘The Dream Songs’ straight through, I’m afraid, without thinking about how times have changed, how what he sees — accurately — as lust in action is what we now see — also accurately — as actionable sexual harassment,” Burt said.

Mr. Bones has the last word as the poem ends:

The restaurant buzzes. She might as well be on Mars.

Where did it all go wrong? There ought to be a law against Henry.

—Mr. Bones: there is.

“Nothing much like the ‘Dream Song’ form had existed before, nothing so out of control, so able to incorporate so many ups and downs, so many highs and lows, without even trying to bring them into some sort of balance,” said Burt.

Berryman’s most anthologized poem, and perhaps his most famous, is “Dream Song 14,” which begins, “Life, friends, is boring” and ends, unforgettably,

And the tranquil hills, & gin, look like a drag

and somehow a dog

has taken itself & its tail considerably away

into mountains or sea or sky, leaving

behind: me, wag.

“As an influence on my poetry, he was overwhelmingly present when I was a flighty teen just starting to write seriously, or over-seriously — I wrote a 30-page paper about him in high school,” said Burt. “And then I tried not to write like him — he seemed irresponsible and self-indulgent, also super-icky in his erotic writing — for about 20 years. And now I’m working on some poems in more impulsive voices, more exuberant personae, and maybe I’m letting him in again.”

Not much remains of Berryman at Harvard. Houghton Library has a few manuscripts, and, in the papers of Robert Lowell, some correspondence between the poets. In one letter, dated Oct. 8, 1953, Berryman wrote: “I am still down on the bottom but thrashing.”

When pressed by The Paris Review in the winter 1972 issue on the topic of the early demises of his literary peers, Berryman prattled off a list of suicides. Vachel Lindsay, Hart Crane, Sylvia Plath, others: “The record is very bad,” he said.

Shortly after, Berryman joined the list.

Listen to Berryman give the Morris Gray Poetry Reading at Harvard in 1962.