Classrooms without walls

When Rebecca Pierre was 9, she would have breakfast each morning with local children attending a nearby summer camp. Day after day Rebecca, who had immigrated to South Boston at age 6, showed up at the camp and sat down to eat. Eventually, a senior counselor took Rebecca’s hand, brought her home, and talked to her mother about getting her enrolled.

That was the beginning of Pierre’s commitment to, and passion for, the South Boston Summer Urban Program (SUP), a camp operated by the student-run Phillips Brooks House Association (PBHA) out of Harvard University.

Twenty-one years later, Rebecca is the director of that camp and a rising senior at Northeastern University. “SUP transformed me. It was a vital piece of my life, and a great part of my growth,” she said.

Rebecca and co-director Monique Takla, a 2014 graduate of Harvard College, oversee the camp as two of the 1,500 student volunteers who help to keep PBHA running. The South Boston camp enrolls 50 campers a summer. Rebecca’s little brother is one of them.

PBHA is the umbrella organization for 83 student-directed programs run by the student volunteers. The association works to meet critical local needs by providing vital resources to the community while helping to nurture public-service leaders. It’s often called “the best course at Harvard” because it provides students with knowledge and experiences that cannot be learned within classroom walls. Its programs serve close to 10,000 low-income people in Boston and Cambridge annually.

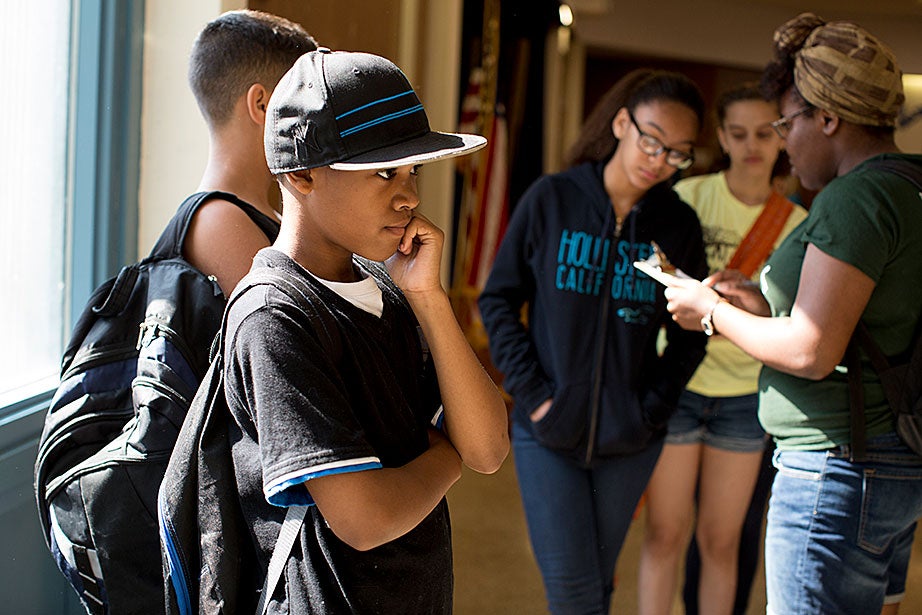

SUP is a set of 10 student-run local camps, held at 12 sites. There are 11 days camps and an evening program in English as a second language for immigrant teens. The programs are staffed by more than 120 college students from various colleges and universities. The college students live in dorms on Harvard’s campus for the summer.

The camps serve more than 900 low-income, at-risk youths ages 6 to 18. The camps last for seven weeks and cost only $120 per child, though no child is turned away because of an inability to pay.

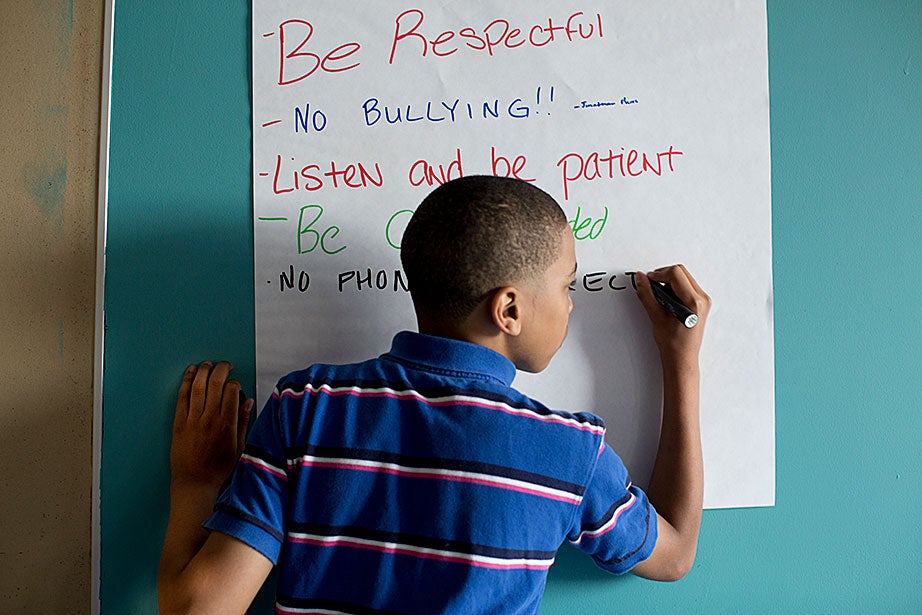

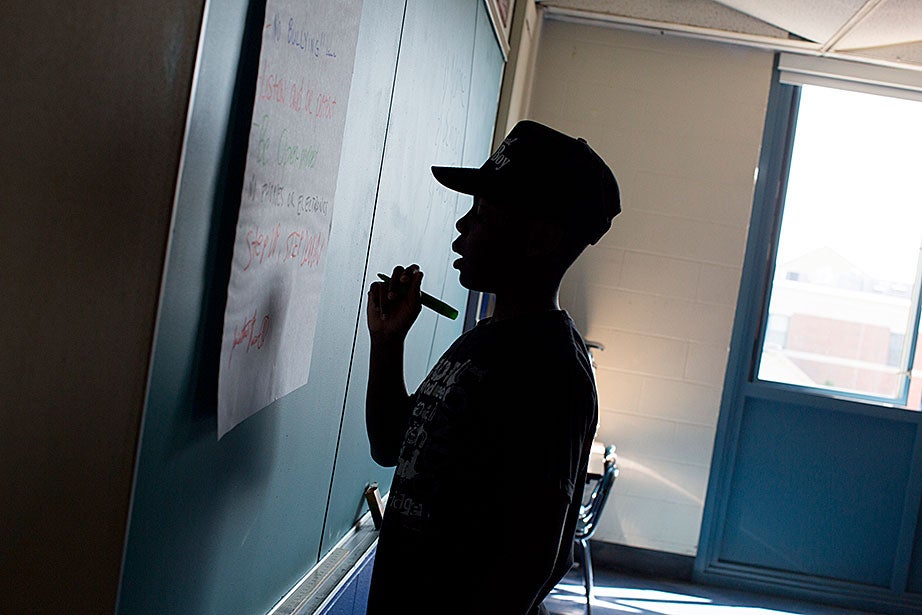

The programs provide a safe, supportive environment for children. They teach violence-prevention activities and serve as an avenue to stop summer learning loss. Research consistently shows that students, particularly those from low-income families, risk losing at least two months of literacy and math skills during the summer. The SUP camps work to stop those losses through activities that blend core academic areas with social and emotional development, and increased community awareness and activism.

“The campers leave here with a real sense of community,” Pierre said. “A lot of what we do has a community angle. We have many different partnerships. We work with Marian Manor, a nursing facility down the road. We partner with South Boston Grows, which teaches the kids about urban gardens and healthy living, and we are constantly talking about how to make healthy life choices.”

The summer programs are structured around curricular, classroom-based enrichment in the mornings and afternoons field trips around Boston.

“PBHA’s SUP camps are a win-win for everyone,” said Maria Dominguez Gray, executive director of PBHA. “Campers and families benefit from enriching programming. Our junior teen counselors are engaged in meaningful employment that offers much-needed job and life skills. And the college students learn so much about themselves, about leadership, effective education, program development, and the various challenges facing urban communities. This is all learning that extends far beyond the classroom.”

In addition to the camps in Boston and Cambridge neighborhoods, there are three that are subject-based. Boston Refugee Youth Enrichment serves 100 children from Dorchester, Mattapan, and South Boston. Refugee Youth Summer Enrichment serves more than 100 high school students from neighborhoods in Greater Boston. These camps target youths from more than 15 countries who have low English proficiency. The camps have been officially accepted by the Boston Public Schools as alternatives to summer school. The Native American Youth Enrichment Program serves more than 40 students and is the only urban camp in Massachusetts dedicated to meeting the academic, cultural, and social needs of local Native American youths.

The Cambridge Youth Enrichment Program serves more than 160 children at three locations. Besides the camp in South Boston, there are also camps serving Chinatown (70 children), the Franklin Field and Franklin Hill housing developments in Dorchester (80 children), Mission Hill (80 children), and Roxbury (80 children). The Keylatch Summer Program serves 80 children living in housing developments in the South End and Lower Roxbury.

Share this article