The glass sea creatures, dating to the 1870s and ’80s, were made by German glass artists Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, who created Harvard’s famed Glass Flowers collection. The sea creatures were made earlier in the Blaschkas’ careers and, unlike the Glass Flowers, which were made solely for Harvard, the sea creatures were widely sold as biological models.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

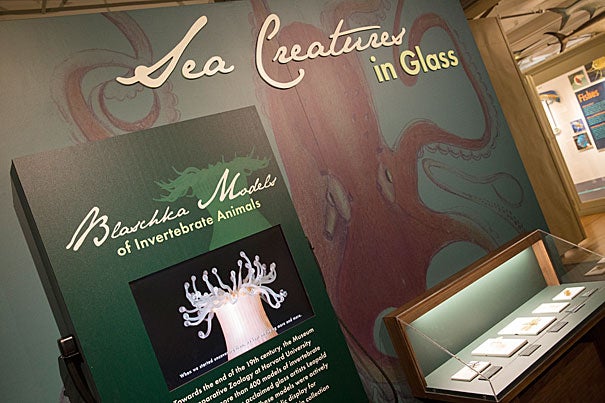

Undersea life, clear as glass

Exhibit at Harvard Museum of Natural History showcases restored Blaschka glass sea creatures

They sold for as little as 50 cents in a scientific catalog in the 1800s, but today are priceless. They were scientific teaching tools, illuminating life under the sea in a way that drawings and preserved specimens couldn’t, but today are works of art.

The Blaschka glass sea creatures are a collection of Portuguese man-o-war, sea anemones, octopuses, and other tentacled marine life that make up a new permanent exhibition, “Sea Creatures in Glass,” at the Harvard Museum of Natural History (HMNH), marking the culmination of an eight-year effort to clean and restore the models.

‘Sea Creatures in Glass’

A glass version of the athecate hydroid, a species of jellyfish. Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Called a phosphorescent sea pen because of its resemblance to a quill pen, this creature is comprised of polyps and able to emit light.

An aeolid nudibranch, or sea slug.

Chrysaora hysoscella, or compass jellyfish, seen here in glass, is rarely seen fully extended.

The 61 specimens are among the 430 marine and terrestrial invertebrates held by Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ), one of three museums that make up the HMNH, which itself is part of the Harvard Museums of Science and Culture.

The glass sea creatures, dating to the 1870s and ’80s, were made by German glass artists Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, who created Harvard’s famed Glass Flowers collection. The sea creatures were made earlier in the Blaschkas’ careers and, unlike the Glass Flowers, which were made solely for Harvard, the sea creatures were widely sold as biological models. Consequently, there are several other collections as well as the MCZ’s.

James Hanken, Alexander Agassiz Professor of Zoology, said the restoration project started shortly after he became MCZ director. An initial assessment of the museum’s collections found the sea creatures stored in shoeboxes and in forgotten corners. Hanken made them a priority, not with the aim of one day putting them on display, but as part of the museum’s broader curatorial mission.

“Our first concern is they were in bad shape,” Hanken said. “Part of our job is to take care of things.”

Museum officials looked for a glass restoration expert who was up to the job of refurbishing irreplaceable specimens more than a century old. They found Elizabeth Brill of Corning, N.Y. Brill was the daughter of a glass chemist, had trained as a marine biologist, and had already worked with the Blaschka invertebrates in other collections. Corning has been a glass-making center for well over a century

“Glass was probably always in my future. I just didn’t know it until I was 29,” Brill said.

What Brill found was a collection badly in need of TLC. Though much of the glass was intact, many of the specimens were made of several parts, held together by glue and wire. Over the years, the glue had deteriorated, and specimens had fallen apart. Curators had carefully set aside the pieces, dusty but whole, leaving Brill with a job that at times resembled putting together a jigsaw puzzle.

“It was really just reassembly,” Brill said. “Over the course of years, curators and professors who used them [to teach] just took care of them, even when better teaching tools came along.”

Working roughly half time for eight years, Brill painstakingly cleaned and reassembled the models, some of which had more than a hundred parts. Though she had originally thought as many as one in five were beyond repair, today, with just a handful still to complete, she said it appears that only three could not be fully restored.

Though permanent, the exhibition will change over time, according to Linda Ford, director of collections operations at the MCZ. That’s because specimens will be swapped out periodically to both allow the public to see a broader selection and to protect individual specimens from prolonged exposure to light, which can degrade them.

Since they were teaching models, the invertebrates are scientifically accurate. The models allowed students to examine lifelike examples that, at a time when the main alternatives were drawings or limp specimens in glass jars, had no equal without a trip to the sea.

“This was one of the ways to see what these creatures looked like in life,” Hanken said. “From a science standpoint, you can get a lot of information from those models.”

The “Sea Creatures in Glass” exhibit and restoration was supported and made possible in part by a gift in memory of Melvin R. Seiden ’52, LL.B. ’55. The exhibit is on display at the Harvard Museum of Natural History, 26 Oxford St., on the Harvard campus. The museum is open 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily. Plan your visit or call 617.495.3045 for admission prices.