Economist Lawrence Summers and foreign policy expert Graham Allison talk about lessons learned from a Chinese research team’s comparison of the conditions around the Great Depression and the recession of 2008. Pictured is Shanghai Tower during its construction, as seen from the Yuyuan Garden, located in the center of Shanghai’s Old City.

Credit: Yimei Zou/CC BY-SA 3.0 License

Chinese economists zero in on crises

Important insights in comparison of Great Depression with recession of ’08, Harvard scholars say

When the global recession hit in 2008, few nations were spared the devastating impact or lingering aftershocks, including the United States and China, the world’s top economic superpowers.

Looking to better understand the crisis and help the Chinese government navigate its challenges, Liu He, M.P.A. ’95, a leading Beijing economist and policy adviser who now serves as minister of the Office of the Central Leading Group on Financial and Economic Affairs, assembled a research team in 2010 to study the circumstances surrounding the Great Depression of the 1930s and the 2008 recession in the hope that the comparison might provide some guideposts.

The resulting analysis, published jointly this month by the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center and the Mossavar-Rahmani Center, identifies a number of instructive similarities between the two crises, including large, nearly-identical income gaps between the wealthiest 1 percent of Americans and everyone else in 1928 and 2007; populist, nationalist, and economic problems that led to poor decision-making by policymakers; and a broadly-felt redistribution of wealth and power on a global scale.

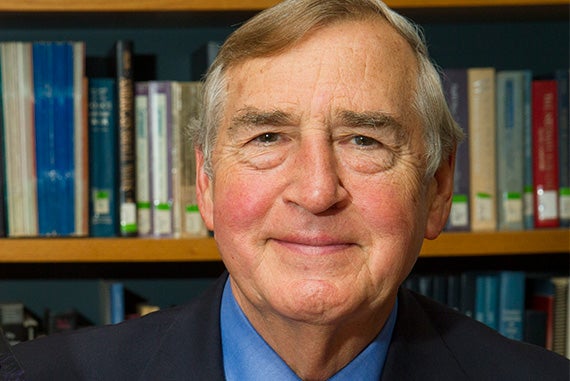

The analysis offers a number of important insights for policymakers and investors around the world, say Lawrence Summers and Graham Allison in the paper’s foreword. Summers is the Charles W. Eliot University Professor and Weil Director of the Mossavar-Rahmani Center. Allison is the Douglas Dillon Professor and the Belfer Center’s director.

The Gazette asked Summers and Allison about the study’s key observations and policy recommendations and how those might inform U.S. economic and foreign policy strategies.

GAZETTE: Which “lessons from China” would you advise U.S. leaders to implement today, and why? Could they work in this political system?

SUMMERS: We should be cautious about extrapolating lessons from China to the United States. China has a very different political system, and an economy at a different stage of development. Certainly, the way China responded very strongly and boldly to the financial crisis with a major program of fiscal expansion — and got very good results — is an instructive lesson for economies around the world.

ALLISON: Liu He recommends China focus on “putting our domestic affairs in order as the foundation for tackling external impacts and realizing our peaceful rise in the world.” This advice resonates with many in the United States who, remembering costly American commitments in Iraq and Afghanistan, are wary about engaging in new adventures abroad.

In Minister Liu’s view, during the financial crisis, politicians were too often “hijacked by short-term public opinion and mired in political gridlock, afraid of breaking ideological constraints.” This also rings true in the U.S., where politics has grown increasingly partisan, often at the expense of wise policymaking. In contrast to the U.S. and Europe, China executed policy decisions rather smoothly and was more able to weather the crisis. He also stresses the importance of “making long-term preparations for structural changes resulting from the crisis,” but this will be difficult in the U.S.

GAZETTE: While the U.S. economy continues to stagnate, China has sustained about three-quarters of its pre-crisis annual growth rate of 10 percent and accounts for a staggering 40 percent of the world’s economic growth since 2008. Is that attributable strictly to China’s post-2008 policy decisions, or are there other forces at work? And could this kind of growth be duplicated in the West?

SUMMERS: No. The largest reason why China is growing so rapidly is that it has substantial opportunities to catch up. The average Chinese standard of living is less than a quarter of the American standard of living. In fact, China’s living standards are now about equal with America’s living standards around 1930. There’s much to admire in what the Chinese have done, but extrapolating their experience to industrialized economies would be a serious mistake.

GAZETTE: While the world seems to be waiting for a new theory or solution to break out of the current economic crisis, Liu’s analysis concludes that whether it returns to form will “largely depend on external luck.” Do you agree and if so, what does that mean going forward?

ALLISON: This is another way of pointing out how difficult it is for economists to predict the future. But as Minister Liu points out, prevention is often the best medicine. It is easier to prevent a crisis, or at least prepare to combat one, than to recover from one that has already occurred. So going forward, it would be wise to focus not just on recovering from the current crisis, but on putting in place measures that will make it easier to mitigate the next crisis.

GAZETTE: China’s strategic realignment since the 2008 crisis — focusing on domestic issues while avoiding major international conflicts, acquiring new technologies from developed countries, investing in infrastructure — are driving an intense political debate right now in the U.S. Under what circumstances, if any, could you envision the U.S. making long-range economic policy decisions free from the constraints of short-term political calculation?

SUMMERS: In a democracy, no decisions are made free from politics. All of the relevant decision-makers are part of a political system. That is as it should be. The U.S. does make long-run decisions — whether it’s our patent system that protects intellectual property, our leading biomedical research at the National Institutes of Health, or long-term investments that support international development, American democracy is capable of making investments that are farsighted and visionary. Certainly it’s true that we need more of that going forward. That’s a challenge for political leaders, but I don’t subscribe to the view that moving away from democracy is the way to get more emphasis on the long run.

ALLISON: I don’t see the U.S. Congress tying its economic policy-making hands any time soon, even if it would be for the greater good.

GAZETTE: The global economic crisis appears to be accelerating a shift in the balance of wealth and power from the U.S. to the Asia-Pacific region. What will that mean politically and economically for the U.S. and for Europe in the coming decade?

SUMMERS: There’s no question that the world is going to be more multipolar and there’s going to be more income and wealth in emerging economies. With less absolute strength, we are going to have to be smarter in the strategies we pursue. It would be a mistake if we responded to these trends by becoming more isolationist. We have to be smarter in our engagement with the rest of the world.

ALLISON: Speaking just about China, it is already the world’s largest energy consumer, top exporter, and top trading country overall. It will soon overtake the U.S. as the world’s largest economy, and according to some estimates, it will overtake the U.S. as the world’s top defense spender before the middle of the century. The question for both China and the U.S. is how to manage this transition peacefully, and how to uphold the current international order that provided the Asian security and economic environment in which China has emerged.