Research librarian Joseph Garver unrolls a Chinese scroll map from 1865, the longest in the collection. It was purchased by John King Fairbank, Harvard’s first full-time professor of Chinese history.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

A map for that

With guidance from students, librarian turns up cartographic gems

The Harvard Map Collection is one of the oldest and largest in the world, with more than 500,000 cartographic items. Every year, students in Professor Stephen Prina’s “Lay of the Land” Visual and Environmental Studies (VES) course take full advantage of its scope, devising a treasure hunt for Joseph Garver, the librarian for research services and collection development, and then traveling to the map collection in Pusey Library to see what he produces.

“This is one of my favorite days of the year,” said Prina, who has been taking classes to the collection since he arrived at Harvard in 2004.

“Ask for a map of anything and we’ll see what comes up,” said Deborah Montes ’16, describing her professor’s assignment. “It was interesting to see what was asked for and what came up.”

Students routinely ask for one-of-a-kind maps — the smallest or the most expensive, for example. This year, the list Garver received included a trail map, a map of poverty, a cartogram, a pop-up map, and a coded map. The students even asked to see a map that was completely wrong.

“The only question I’ve seen before is something like the longest map,” Garver said, pointing to a Chinese scroll from 1865 that unrolled to more than 10 feet in length.

To fulfill requests, Garver displayed maps, atlases, and globes dating to the 15th century. Students oohed when Garver unfolded a pocket-sized guide to the Oakley Hunt, which directed foxhunters through roads, woods, and — in case of distraction — local pubs. They laughed when he showed a “very unofficial” map of the United States as viewed by perpetually sunny Californians.

Garver also presented a highly valuable map of Greece that was created in 1797 to trace the history of Greek independence. He explained that the Ottoman Empire destroyed many of its copies, so only a few exist. Greece has one; Harvard’s is probably the sole version in the United States.

“I like listening to Joseph,” said Gabriel Jandali-Appel ’16, who requested the Grecian map. “He’s always remarkably intelligent.” Though many members of the class were making their first trip to the collection, Jandali-Appel has spent time working in it. Still, he had not seen many of the maps Garver presented. “I didn’t know what to expect and I was pleasantly surprised,” he added.

Michael Wang ’14 was impressed by the detail and craft in the work. “There’s a lot more artistry involved in maps than I’d previously imagined,” he said.

He was not alone. “Lay of the Land” focuses on pursuing and responding to the horizontal in art, so students were prepared to note the collection’s aesthetic qualities.

“I asked for the map of the ocean floor,” said Montes. “I really liked that one. It was hand-painted with such incredible detail. It was such a beautiful map.”

Monica Palos ’15 reflected on the skill, time, and patience required of mapmakers, saying, “Looking at different types of maps is always very interesting to me. The artistry that goes behind it — hand-painting, hand-drawing, going into digital — that’s something that impresses me.”

“Map collections do tend to get people interested in art,” Garver said, though the range of patrons doesn’t stop there. He has hosted genealogists, epidemiologists, scientists, doctors, and historians.

Similarly, many in Prina’s class are artists, but their concentrations vary from VES to government to human evolutionary biology.

“It’s always a vastly diverse group of people that come together when we discuss these works, whether it be film, an essay, or a map,” said Jandali-Appel. “I just like the variety of opinions and ideas and it’s always really inspiring. It was cool, right? Aren’t those maps neat?”

Share this article

Different directions

Ernest Dudley Chase’s satirical “The United States as viewed by California (Very Unofficial)” puts Harvard on the map. Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

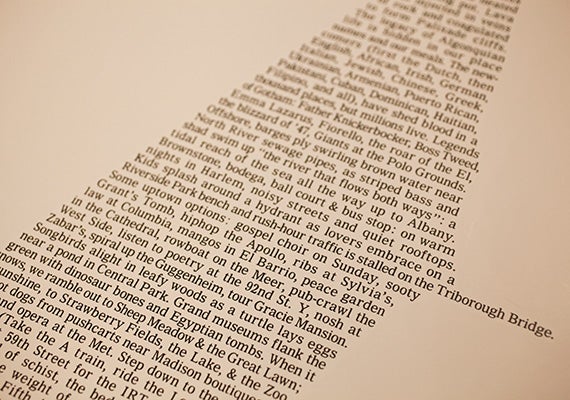

Howard Horowitz’s 1997 Manhattan wordmap takes a personal look at how he remembers the city.

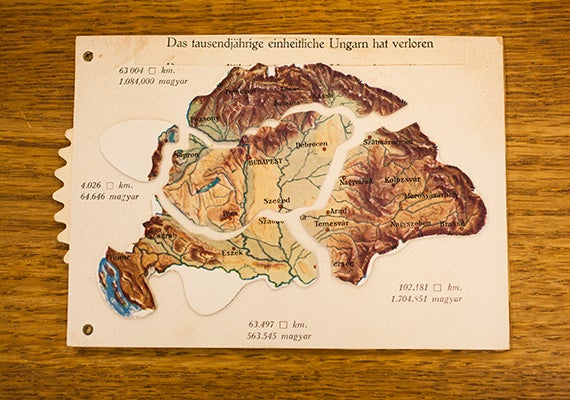

A postcard map gives a movable view of Hungary after the Treaty of Versailles.

A detail of painted birds appears on a facsimile of a 1502 map showing Portugal’s recent discoveries in Brazil, Africa, and the Indies.

The encasing for one of the longest scroll maps in the collection is pictured up close.

Research librarian Joseph Garver (center) provides historical context during a presentation to Gabriel Jandali-Appel ’16 (from left), Stephen Prina, Monica Palos ’15, Jesse Aron Green, Deborah Montes ’16, Michael Wang ’14, Leonie Marinovich, and Greg Marinovich.