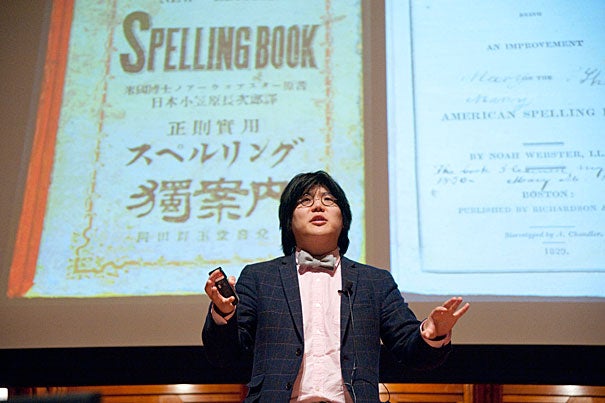

As part of the Harvard Horizons symposium at Sanders Theatre, Ph.D. student Hansun Hsiung argued that the latest education craze of distance learning began with the printing of the first international textbooks in the 18th century.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Style and substance

Harvard Horizons symposium highlights student research, aids presentation skills

Distance learning is typically thought of as a relatively modern innovation — accelerated through the Internet and online classes.

But Hansun Hsiung, a Ph.D. student in East Asian languages and civilizations, isn’t convinced.

As part of the Harvard Horizons symposium, May 6 at a packed Sanders Theatre, Hsiung argued that distance learning began significantly earlier, with the printing of the first international textbooks in the 18th century.

“The textbook as we know it was a fairly recent invention,” developing only in the second half of the 18th century and rising in use over the course of the 19th, Hsiung told the audience.

For readers, he said, the access such books provided was considered in the same light as online learning is today. Access to the textbook “promised that every man could be his own teacher,” Hsiung said. “No matter who or where you were in the world, as long as you had the right textbook,” you — as a reader — could share in long-distance learning.

Created this year by the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS), the Harvard Horizons initiative highlights top research by doctoral students. One of the goals is to foster a greater sense of intellectual community across Harvard’s graduate schools. Another: to help students develop crucial presentation skills. The culmination of the initiative was an afternoon symposium in which eight Ph.D. students each offered five-minute presentations, styled on the popular TED talks, about a specific aspect of their current research.

Along with Hsiung, other presenters included:

- Edgar Barroso, music, “Enhancing Music, Social, and Entrepreneurial Innovation through Trans-Disciplinary Collaboration”

- Stephanie Dick, history of science, “Aftermath: Following Mathematics into the Digital”

- Alex Fattal, anthropology, “Guerrilla Marketing: Information War and the Demobilization of FARC Rebels”

- Fenna Krienen, psychology, “Big Brain Science: Strategies for Mapping the Human Brain”

- Aaron Kuan, applied physics, “Graphene Nanopores for Single-Molecule DNA Sequencing”

- Liz Maynes-Aminzade, English, “Macrorealism: How Fiction Can Help Us Understand a Networked World”

- Jeff Teigler, medical sciences, “Building Better Vaccines by Learning the Language of the Immune System”

GSAS Dean Xiao-Li Meng, Ph.D. ’90, hosted the event, which was attended by Provost Alan M. Garber ’76, Ph.D. ’82, and FAS Dean Michael Smith. In a video address, President Drew Faust emphasized the importance of the symposium.

“Communicating about one’s work outside of one’s discipline is an essential skill for scholars and researchers in the 21st century, and the women and men you are about to see are persuasive and powerful presenters,” she said. “Their presentations exemplify one of the finest gifts universities give to humanity: individuals capable of making new and significant contributions to the world of knowledge.”

While the presentations may have looked simple, they were the result of weeks of work.

After being selected from 55 applications, the eight members of the inaugural class of the Society of Horizon Scholars underwent a five-week training course that included mentoring sessions by Harvard faculty members and experts from the Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning. The sessions, which focused on voice and on visual presentation skills, among other topics, were led by Laura Frahm, an assistant professor of visual and environmental studies, and Pamela Pollock, an assistant director of the Bok Center.

Harvard Horizons was the brainchild of Shigehisa Kuriyama, chair of the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations.

“One of the big challenges at Harvard is this: the wealth of talks and presentations constantly occurring on campus makes it hard to reach audiences beyond one’s division, or sometimes even beyond one’s department,” Kuriyama said. “Because the competition for attention is so intense, the ability to communicate one’s ideas lucidly and crisply is becoming an even more fundamental skill.”

Equally important, Kuriyama said, have been the social aspects of the program. Given the focus and time research demands of students, it’s unlikely any of the Horizon Scholars would otherwise have met each other.

“I think that’s one of the things that they found most invigorating, the social bonding and the intellectual exchange,” he said. “All of our students are curious, and eager to learn about other fields. But they have relatively few opportunities to speak with students in other divisions, especially students who have the ability to explain their research in terms that are clear and compelling to the nonspecialist. This program is designed to give them those opportunities.”

Meng said he sees the initiative as filling an important role in helping provide much-needed training in the communication skills students require — as teachers, as scholars applying for grants and fellowships, and in their professional careers, whether in academia or in policy, corporate leadership, or industrial research. Going forward, Meng said, he hopes to explore how to expand the program to ensure more graduate students receive the benefit of such training.

“We now have about 10 departments that include various courses on how to communicate,” he said. “Regardless of what your career may be — some of these students may become professors, and others may go into business or government — communication is a skill that is absolutely critical.

“If you look at how society is evolving, we’re all multitasking, every one’s attention span is getting shorter,” Meng continued. “In addition to possessing deep expertise in their field of study, our students need to be able to deliver an elevator speech, and that’s a skill that has not traditionally been emphasized. They need to be able to talk with a variety of audiences, across a variety of disciplines, about what they do and why it’s important.”