Karl Pillemer’s research began with a simple question: “What are the most important lessons you have learned over your life?” One unanimous refrain included just three simple words: Life is short.

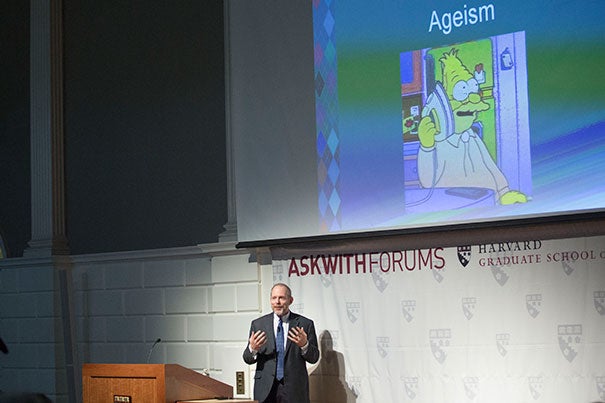

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Lessons from the long-lived

Researcher says the elderly are pragmatic ‘masters and mistresses of resilience’

Not long ago, Karl Pillemer had a revelation.

A gerontologist with close to 30 years of experience, Pillemer, who is director of the Cornell Institute for Translational Research on Aging, realized that his research was “entirely focused on older people as problems.”

“It’s something a little bit embarrassing for me,” Pillemer told a crowd at the Harvard Graduate School of Education on Wednesday, as he described his work in areas involving chronic pain, elder abuse, Alzheimer’s, dementia, and problems of family care giving. “I got to a point in this revelation that it seemed like I was writing the ‘Book of Job’ for old people.”

But Pillemer, who is also a professor of human development at Cornell University, remembered that his job also engages him with “vibrant, engaged, healthy, exciting, and active older people.”

The paradox intrigued him, as did the countless surveys conducted over the past 10 years revealing that the elderly tend to be significantly happier than people decades younger. That knowledge, combined with what he called a “disturbing sense that we lost an age-old and time-honored activity of not just asking older people for stories, but asking for their actual advice for living,” led him to create the Legacy Project, a study of almost 1,500 people, ranging from their 70s to over 100, who shared their wisdom about life. His work resulted in the 2011 book “30 Lessons for Living: Tried and True Advice from the Wisest Americans.”

For Pillemer, the notion of asking for life’s lessons from those who have lived through wars, the Great Depression, poverty, exile, and immigration is particularly relevant today as the United States struggles with a war on terror and a floundering economy.

“You wouldn’t go to older people to find out how to program your DVR, but older people are our most credible source of information on how to live through hard times. They are masters and mistresses of resilience, and that’s something we can really learn from.”

His research began with a simple question: “What are the most important lessons you have learned over your life?” Respondents included homemakers, entrepreneurs, and even a former Tuskegee airman, and their answers touched on topics like marriage, children, money, work, aging, and health.

One unanimous refrain included just three simple words: Life is short. A retired engineer told Pillemer that “it passes in a nanosecond.” A 99-year-old woman said, “I don’t know what happened, but the next thing you know you are 100.”

That firm appreciation of life’s fleeting nature led to a list of surprising lessons for Pillemer and his research team. Though many survey participants had lived through hard economic times, instead of urging younger people to get steady, well-paying jobs, they consistently said, “Do something you enjoy.”

“Based on this extremely acute awareness of the shortness of life, everybody argued you should find work you love; work ought to be chosen for its intrinsic value, and for its sense of enjoyment, sense of purpose. And life was much too short to spend doing something you don’t like, even for a few years.”

Similarly, respondents surprised Pillemer when he asked them to name their biggest regrets. Instead of listing concerns like affairs, addictions, or shady business dealings, almost unanimously they answered: “I wish I had not spent so much time worrying.”

“The idea behind that again related to shortness of life. … The argument they make is that the mindless and ruminative worry over things one can’t control so effectively poisons life that it’s a waste of a precious lifetime.”

Another standout lesson from the survey involved the notion of being responsible for one’s own happiness. While it sounds like a cliché, said Pillemer, “It’s a critical part of their lived reality, and their argument is as follows: Younger people tend to be happy ‘if only’. … Their view from later life is that this has to morph into being happy in spite of things.”

He illustrated his point with a video clip of Helga, an octogenarian who lost her middle child, a vibrant young woman nicknamed “Bubbles,” in a plane crash.

“For two years, I guess I tortured myself and the rest of my family, and then one day I said to myself, ‘O.K. you have to stop this.’ … It doesn’t mean you forget, or you let it go,” she said, “but you have to think of the living ones.”

Instead of offering advice like “eat your vegetables,” “go to bed early,” or “don’t smoke,” participants in the survey consistently responded, when asked about their health: “Treat your body like you are going to need it for 100 years.”

“What the oldest Americans know is that in your dreams you are going to drop dead,” said Pillemer. The elderly, he added, understand that modern medical technology means people with unhealthy lifestyles are “sentencing themselves to 20 or 30 or 40 years of chronic illness.”

Pillemer, who is at work on a new study about the lessons that can be learned from long-lasting marriages and relationships, is also developing a curriculum aimed at getting schoolchildren and youth groups to create their own legacy projects.

As a parting thought, he made a final plea to the educators in the room, urging them to reach out to older generations for wisdom and advice before it’s too late. “We aren’t making use of them in any educational way, and that seems to me really preposterous. That’s a major education opportunity that we are missing.”