Stability amid revolution

Doctoral student plumbs China’s strength throughout war, turmoil

Part of a series about Harvard’s deep ties to Asia.

JINAN, China — As a German diplomat in Africa, Daniel Koss saw his share of unstable governments. But given the continent’s poverty, factionalism, and history of colonialism, the situation was understandable.

What he didn’t understand was China.

The Asian giant, growing ever larger on the world stage while Koss was in Africa from 2004 to 2006, was once beset by many of the same problems. It was colonized by European powers and by Japan. It suffered waves of violence during the 1937 Japanese invasion, the civil war between nationalists and Communists, and the Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976.

“I’m interested in political order and how you create political order,” Koss said. “Coming from Africa, I wondered, ‘How is this country stable?’ It’s a Communist country that’s not really Communist anymore, so what makes it stick together?”

Koss believes the answer may lie with the Chinese bureaucracy, which has endured trials and turmoil for 1,000 years, deep into the imperial past. If he’s right, that bureaucracy represents a stable foundation upon which the Communist Party’s networks of members operate, working together to create a stable state.

Koss, a doctoral student in Harvard’s Government Department, is nearing the end of his second six-month stint in China’s Shandong Province, whose provincial capital, Jinan, is 250 miles south of Beijing and has a population of more than 4 million. Koss has been living a somewhat transient life in Shandong, bouncing between hotels, a room borrowed from a university faculty member, and an academic guest house as he visits archives, speaks with local residents, and travels to view key sites.

From German government to Harvard

Koss gave up a career in Germany’s Foreign Ministry to come to Harvard. After a two-year stint in the embassy in Cameroon that began in 2004, he moved to the permanent mission to the United Nations in New York when his wife, Jie Li, entered graduate school at Harvard. He eventually applied to Harvard himself.

“I really like academic life,” said Koss, whose work is supported by the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies’ Desmond and Whitney Shum Fellowship. “There’s much more freedom to ask the questions I want to ask, and to ask deeper questions, too.”

Koss entered Harvard to study international relations, but switched to political science after taking a course from his eventual adviser, Henry Rosovsky Professor of Government Elizabeth Perry.

“I was blown away by how much you can do with political science,” Koss said.

In China, Koss has had ups and downs with his research. There are times when the archives are welcoming, the documents he seeks are available, and the people he meets vividly recall the Cultural Revolution. But at other times, he finds archives closed, documents unavailable, and people suspicious of the questions he’s asking. He has had a laptop stolen — less than disastrous because he’d backed up the data — and was once interrogated for nine hours while crossing the border because of papers he’d purchased in a local market.

His first visit presented other challenges. He had learned to read Chinese before going overseas, but initially found it difficult to interview officials. So he spent the early part of that visit practicing Chinese on the job, improving his ability to converse, which got him more access to people and documents. After his first six-month visit, his biggest problem wasn’t the field conditions, but his confusion over what he had learned and where it might lead.

He returned to Cambridge, talked with his doctoral adviser, and sorted out his research direction.

“Daniel is one of an extraordinarily talented group of Harvard Government Department doctoral candidates doing pioneering grassroots field work in China to explain the remarkable differences in policies and politics among local governments,” Perry said. “Daniel’s project is notable for its historical depth. It is a very exciting exploration of how imperial and revolutionary legacies may continue to shape contemporary state-society relations.”

Koss has gotten support from several faculty members at Shandong University in Jinan, at the history department and at the School of Public Administration on the Hongjialou campus. The head of local government studies at the university, Fang Lei, has offered support, as well as the all-important introductory letters needed to access local archives.

Fang said foreign scholars such as Koss can work on subjects that local Chinese scholars may not be able to, so their work is useful within China too.

Three layers of study

Koss said his work involves three layers. The first, largely conducted at the Harvard-Yenching Library, explores the imperial bureaucratic legacy stretching back 1,000 years. The imperial Chinese bureaucracy was renowned for efficient administration of the vast country. It had an examination system that helped ensure that officials were qualified and a personnel appointment system that was able to pick local governors who were loyal to the leadership, talented enough to do the job, and who wouldn’t raise the ire of the local people.

“The basic problem [today] is the same,” Koss said.

The second layer of his work examines the roots of the Communist Party’s political network, which varies in strength from province to province. He believes that party strength came not from idealistic fervor, but from patriotic sentiment aroused by the Japanese invasion in 1937. By looking at which provinces have the highest party membership and comparing them to the extent of Japanese occupation, he was able to draw nearly a one-to-one correlation between occupation and party strength.

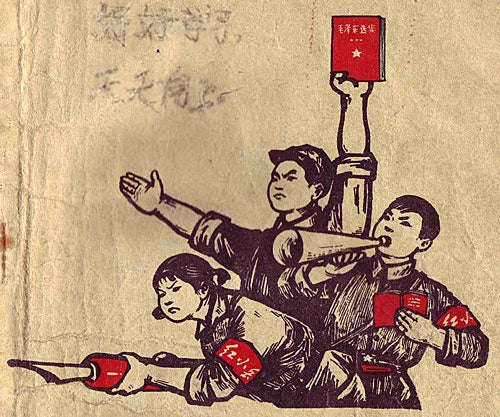

The third layer looks at the later chaos of the Cultural Revolution, which began in 1966 and stretched until leader Mao Zedong’s death in 1976. Those years, during which the revolutionary Red Guard moved against China’s own institutions, were particularly difficult for the bureaucracy, which was specifically targeted by the violence, which killed between 750,000 and several million.

Koss’ work shows that the Cultural Revolution didn’t undo China’s bureaucratic legacies, but eventually made the state stronger as bureaucrats learned to cope with rebellion and to continue government operations even amid turmoil. Despite the violence, the bureaucracy ground on. He has found posters that reminded protesters to protect water quality, and brochures whose publication alone affirms that bureaucratic functioning continued. Perhaps most telling, a search of tax records shows that despite the turmoil, tax receipts in Shandong Province during the most difficult year fell just 2 percent.

“Words like ‘anarchy’ and ‘civil war’ come to mind, but it’s wrong. On the streets, that was the experience, but the state continued,” Koss said. “The bureaucracy was still functioning. It’s very resilient. If there’s a problem, you know the government will keep running.”