The man who wrote that “all men are created equal” owned hundreds of black men throughout his lifetime, noted Wilson J. Moses, as he presented the second of three lectures on “Thomas Jefferson and the Notion of Liberty.” But Jefferson also suggested that “there is a moral instinct and the black people are not lacking in this,” Moses said. The lecture series continues today at the Barker Center at 4 p.m.

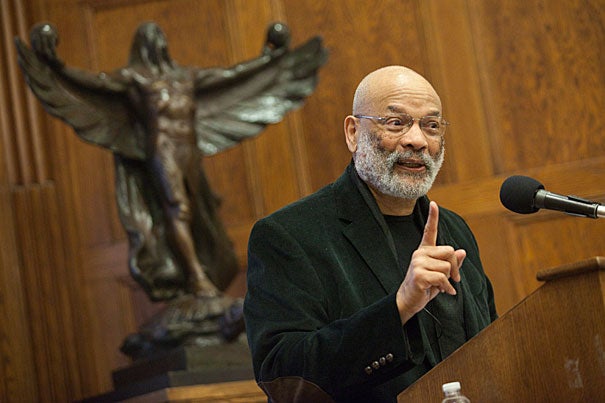

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

The ‘last Renaissance man’

Historian probes stark contrasts of Thomas Jefferson’s character, intellect

Placing Thomas Jefferson in the intellectual life of his times may best be understood by quoting the third U.S. president himself on the character of the first, George Washington, according to an American historian:

“His mind was great and powerful, without being of the very first order; his penetration strong, though not so acute as that of a Newton, Bacon, or Locke; and as far as he saw, no judgment was ever sounder.”

“Thomas Jefferson has been called the last Renaissance man,” said Wilson J. Moses, the Ferree Professor of American History at Pennsylvania State University, as he kicked off “Mammoths, Meteors, and Mulattoes.” The Wednesday lecture was the second of three on “Thomas Jefferson and the Notion of Liberty,” part of the Nathan I. Huggins series sponsored by the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research.

“It’s been said Jefferson was the last man to engage with success all the knowledge of his time,” as a statesman and student of letters, language, architecture, religion, philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, and natural sciences, Moses said.

He was also “certainly a character of flexible values, like Niccolò Machiavelli,” and has been unavoidably and problematically tied to racism. The man who wrote that “all men are created equal” owned hundreds of black men throughout his lifetime and compared them to orangutans in his only published book. But Jefferson also suggested that “there is a moral instinct and the black people are not lacking in this,” Moses said, and knew from Volney’s “Ruins of Empires” about the “race of men now rejected from society for their sable skin and frizzled hair [who] founded on the study of the Laws of nature, those civil and religious systems which still govern the universe.”

A detailed record-keeper, Jefferson left notes of what he saw, read, and heard, though his papers offer little critical analysis — even of his political contemporaries, on whose ideas his commentary “was scanty and often superficial,” Wilson said. His reading tastes reflected a solid grounding in the classics. He enjoyed music, and would have known that “The Marriage of Figaro” was based on a play that dealt with institutionalized rape and that the text of “Don Giovanni” addressed the kind of sexual exploitation and class conflict familiar to him in Virginia.

Jefferson’s mind was “brilliant and inquisitive” but lacked the military and financial acumen that contributed to Washington’s success, the practical knowledge of Frederick the Great, or the scientific expertise of Benjamin Franklin. Jefferson “is rightly praised for having overcome the isolation and provincialism of his early life,” Moses said. He was placed in a Latin school at the age of 9, and later developed close relationships with supportive professors. At 17 he met Patrick Henry, a rapid intellect accepted to the Virginia bar after only six weeks of study, and was both entranced and appalled by the older man.

“I suspect Jefferson was always somewhat jealous of Patrick Henry,” Moses said. Henry’s brief, best-known phrases — “If this be treason, make the most of it” and “Give me liberty or give me death” — may have contributed as greatly to the philosophy of the American Revolution as Jefferson’s more thoughtful words.

And although Jefferson became “the symbol for all ages as the author of the Declaration of Independence, regardless of how despotically he exercised his powers as the master in Virginia,” his contribution to the work may have lain more heavily in drafting than in theory.

Moses said Jefferson’s only book, “Notes on the State of Virginia,” still commands respect, “although it reveals patterns of thinking more traditional than revolutionary,” like discomfort with the idea that species such as the North American mammoth could become extinct or that meteors could fall from the sky. Such questions, Moses said, did not conform to the Newtonian idea of an orderly universe.

The Newtonians were also troubled by the relationship of nature to God. Moses said Jefferson rejected portions of the New Testament that were inconsistent with his own theories, but nonetheless believed in the deity and thought that only “a revolution of the wheel of fortune” had given white men control over Africans.

“Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just; that his justice cannot sleep forever,” Jefferson wrote.

“Thomas Jefferson and the Notion of Liberty” concludes today with “Private Vice and Public Virtue” at 4 p.m. in the Thompson Room of the Barker Center, 12 Quincy St., Cambridge.