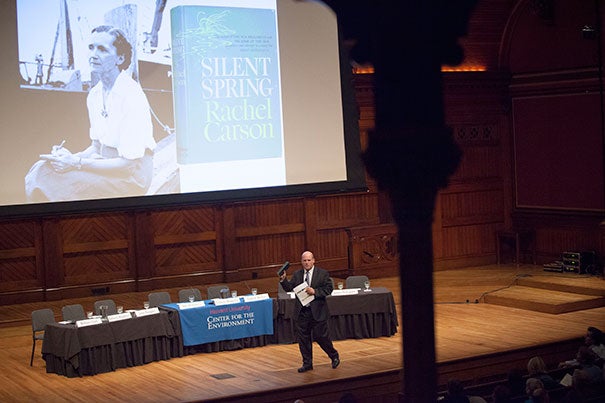

“This was a book, in some ways, that really changed at least the U.S. and perhaps even the world,” said Daniel Schrag, director of the Harvard University Center for the Environment, who hosted “Science and Advocacy: The Legacy of Silent Spring” at Sanders Theatre.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘Silent Spring,’ 50 years on

Environmentalists, faculty mark lessons of Carson’s seminal book

Writer Rachel Carson’s feared “silent spring” — the nightmare scenario in which widespread chemical spraying wipes out insects and the birds that feed on them —has not happened. But the world today faces no shortage of environmental challenges that demand the sort of intense energy and activism that she embodied.

That was the message of a panel of experts, writers, and activists Thursday at Harvard’s Sanders Theatre to mark the 50th anniversary of the publication of Carson’s seminal book that chronicled the environmental harm wrought by pesticides and warned against their overuse.

The publication of “Silent Spring” often has been credited with galvanizing a generation into action against environmental degradation, with sparking the start of the modern environmental movement, and with leading to a ban of the pesticide DDT in 1972.

“This was a book, in some ways, that really changed at least the U.S. and perhaps even the world,” said Daniel Schrag, director of the Harvard University Center for the Environment, and the event’s host. “It’s … an impassioned plea for a change in the course of human history.”

“Science and Advocacy: The Legacy of Silent Spring” was sponsored by the Center for the Environment and featured New York Times columnist Andrew Revkin, Natural Resources Defense Council President Frances Beinecke, and writer and activist Bill McKibben.

It also featured several Harvard faculty members, including William Clark, the Brooks Professor of International Science, Public Policy and Human Development at the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS); Rebecca Henderson, McArthur University Professor; Sheila Jasanoff, Pforzheimer Professor of Science and Technology Studies at HKS; James McCarthy, Alexander Agassiz Professor of Biological Oceanography in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS); and John Spengler, the Akira Yamaguchi Professor of Environmental Health and Human Habitation in the Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH).

Schrag, the Sturgis Hooper Professor of Geology and professor of environmental science and engineering, opened the event by reading passages from the book, in which Carson warned that humanity’s drive to subdue nature was bearing unintended consequences that threatened humanity itself.

Panelists said that Carson’s power came from a combination of factors. As a biologist, the science that she presented in the book was solid. And as a writer, her prose presented the situation in a way that was not only accessible to readers but also moved them to action.

Revkin, who has written about the environment for decades, said what struck him in reviewing the book was her treatment of uncertainty, a key element in any scientific debate. Carson was frank with readers about what experts knew and what they didn’t know, Revkin said, showing her readers respect and trusting that they could handle uncertainty. She let them make up their own minds, something missing from many discussions of science today, which tend toward black and white.

“She was able in this book to allow the reader to have authority to worry. She wasn’t telling them to worry,” Revkin said.

Revkin also highlighted the opposition that the book generated, and that continues today. Some critics suggest that the reduced use of DDT and other pesticides cost human lives, particularly in the fight against malaria.

Remaining objective under pressure

Panelists also discussed the tension that scientists feel between the pressure to remain objective and the public’s need for informed leaders, like Carson, to push for science-based reform.

McKibben, who authored 1989’s “The End of Nature,” the first book on climate change written for a general audience, said Carson’s impact extended beyond her book. Though riddled with cancer, which would lead to her death just two years after the book’s publication, Carson remained a vocal advocate of the ideas laid out in it.

McKibben said that people have different identities, at work and outside of it. One identity is that of a citizen, and it is in that role that people should work for change, even if advocacy may seem contrary to other roles. At Harvard, McKibben said, the University’s efforts to erect green buildings doesn’t go far enough in fighting climate change, and he voiced support for efforts to have the endowment divest oil company stock.

Clark said that prominent scientists sometimes fail to examine whether they’re living in ways consistent with the sustainability value that they espouse — flying around the world on carbon dioxide-spewing aircraft to give speeches when other alternatives exist. He cautioned that scientists and others supporting sustainability — even a noted climate change champion like former Vice President Al Gore, whose energy-gobbling home generated accusations of hypocrisy — can suffer when they don’t live according to stated beliefs.

“I think we let ourselves off the hook too easily,” Clark said.

Some panelists talked about the personal impact of Carson’s writings. McCarthy said Carson’s earlier book on the ocean, “The Sea Around Us,” was also eloquently written and widely read by a generation of oceanographers, including him. Spengler detailed how the echoes of Carson’s writing reached him in recent years, reminding him of a long-ago day at play in fields overflown by a biplane that sprayed him and his companions. Recent blood tests, he said, showed that the derivatives of DDT sprayed that day remain in his body.

Lessons worth teaching again

Despite the unquestioned impact of “Silent Spring,” some of its lessons appear to need reteaching. A few years ago, Spengler studied the high incidence of asthma in Boston public housing, tracing it to high levels of pesticides sprayed in the buildings. His work prompted adoption of integrated pest management techniques in the buildings and highlighted the importance of continued vigilance.

Though Carson came under intense attack from the chemical and agricultural industries and their supporters, she never wavered, Beinecke said. If she were alive today and saw the thousands of chemicals, some unregulated, that surround us and viewed the dangers of climate change, she’d likely focus her advocacy there.

“Would she be distressed?” Beinecke asked. “I’m sure she’d share the distress we all have, but I think she’d be motivated’’ to act.