Conservation intern Allison Holcomb, a master’s degree student in the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation, examined Austen’s letters and wrote a detailed “proposal record” for repairing each. It’s a technical job, but a private thrill, said Holcomb. She emailed a friend about the project, filling in the subject line with exclamation points.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Sensibly saving Jane Austen

Two of her fragile letters, owned by Harvard, undergo painstaking repair

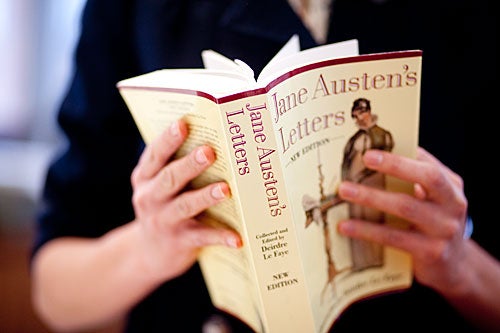

British romantic novelist Jane Austen died penniless on July 18, 1817, at the age of 41. Four of her six novels were already in print, but her obscurity was so deep that it was not until December that Austen was identified as the author. In life, fortune and fame eluded Austen, a minister’s daughter whose writing is now widely celebrated for its wit and realism.

But fame did follow. A collected edition of Austen’s novels appeared in 1833, and they have been in print ever since. By 1880, Austen was the subject of a public adulation so wild that Victorians called it “Austenolatry.” In the 21st century, this fervent literary fandom remains unchecked.

But Austen’s fame is a problem for scholars in search of scarce clues to her life. Consider, for one, the fate of her letters. By some estimates, Austen wrote 3,000, but only about 160 survive.

Harvard’s Houghton Library owns five complete letters and one fragment. They are little storms of gossip, fashion, and drawing-room intrigue — novels in miniature that show off Austen’s ready humor and astute powers of observation.

Even in their lightness, they remain valuable to scholars. In the fall of 2010, Harvard Assistant Professor of English Andrew Warren arranged for his class to see one of the Austen letters, because the experience “draws us into Austen’s social world, which after all is the inspiration for the novels,” he said. “The world of the novels is uncannily close to the world depicted, or rather enacted, in the letter.”

For Harvard, it’s only a matter of sense and sensibility to treat the Austen letters well, with temperature and humidity controls, flat storage in acid-free folders, protection from ultraviolet light, and limited physical access.

Add to those protections the expert ministrations of the Weissman Preservation Center, an arm of the Harvard University Library. Last month, experts there finished restoring two of the University’s Austen letters, one written in 1805 and the other in 1813.

Both are “autograph letters,” handwritten missives addressed to Austen’s sister and lifelong confidante Cassandra. They were gifts from Amy Lowell, the Brookline poet and John Keats biographer who in 1925 bequeathed to Harvard an extensive literary collection of books and autographs. (A Houghton exhibit of the Lowell collection is planned for the fall.)

The letters, on cream-colored writing paper, are in remarkable shape, despite the intentional creases common in Austen’s day, when letters were folded for mailing. (The modern envelope appeared nearly a century later.)

The two letters are also full to the edges with Austen’s neat, small handwriting, in lines as straight as a ruler. “Keats wasn’t so tidy in his letters,” said Debora Mayer, the Weissman’s Helen H. Glaser Conservator. (Lowell’s Keats collection is ample and comprehensive.) But however neat the handwriting, she added, the Austen letters illustrate one joy of the conservation business: the thrill of proximity to the greats of history and literature.

“We’re artists, we’re historians, and we like to be connected,” said Mayer of conservators. “Working on objects connects us, very much so … to another place and time.”

Closest to the Austen letters was Harvard conservation intern Allison Holcomb, a master’s degree student in the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation. Late last year she examined the letters and wrote a detailed “proposal record” for repairing each. It’s a technical job, but a private thrill, said Holcomb. She emailed a friend about the project, filling in the subject line with exclamation points.

Holcomb showed her tools, which illustrate the cleanliness, care, and precision required for literary conservation: specialized blotters to protect text, needle-like awls, delicate brushes, magnifying glasses, long-fibered Japanese tissue for mending tears, surgical scalpels, and a stainless steel tool for turning pages — aptly called a “micro spatula.”

Before treatment, Holcomb examined the Austen letters under magnification, traced water marks to determine the origin of the paper, took documentary digital images (a step repeated after restoration), and used “raking” (oblique) light to search for minor distortions in the paper. Conservation work, said Mayer, first involves “looking closely and intently.”

During the treatment, Holcomb used vinyl eraser crumbs to gently clean the letter surfaces. (Using water was out of the question; it would accelerate the destructive chemistry of the iron gall ink common to Austen’s era.) But she left the graphite marks within each letter untouched, because they are editorially significant attempts on the part of early editors to mark logical paragraph breaks. To finish, Holcomb removed old repairs, flattened bent corners, and fixed several tears.

The two letters bring Austen alive — observant, funny, gossipy, and irreverent. The 1813 missive closes with what might be a message to anyone still under the spell of Austenolatry today. “Now I think I have written you a good sized Letter & may deserve whatever I can get in reply,” she wrote. “Infinities of Love.”

Share this article

Yours truly Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Conservationist

Allison Holcomb, an intern at Harvard Library’s Weissman Preservation Center, repairs two 19th-century letters written by Jane Austen to her sister, Cassandra.

Lettres de Austen

Holcomb has read the translations for each and refers back to them when necessary.

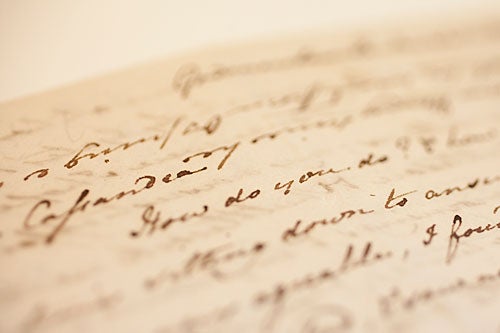

How do you do?

This letter from Jane to Cassandra begins halfway down the page, as was the practice, with “How do you do?” It is written on hot-pressed paper in corrosive iron gall ink.

Worlds ago

Holcomb, who attends the Winterthur Museum at the University of Delaware, uses a micro-spatula to repair this letter written in 1805.

Tricks of the trade

Because her field of conservation is so small, Holcomb appropriates materials from other fields. The tweezers, water pen, and micro-spatulas are all utensils she is using on this current project.

Flourish

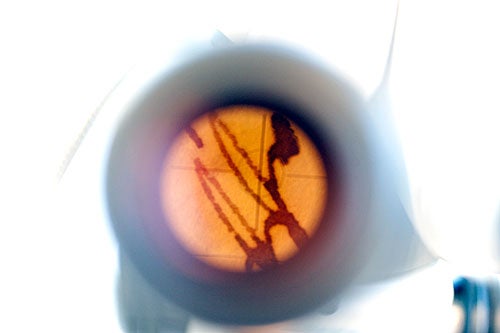

Through the microscope Holcomb can see minute details of the lettering.

Tedious work

Using her fingers and eraser crumbs, Holcomb cleans each letter.

Near perfect

This letter, containing a previous repair (upper left), will be restored to its original form.

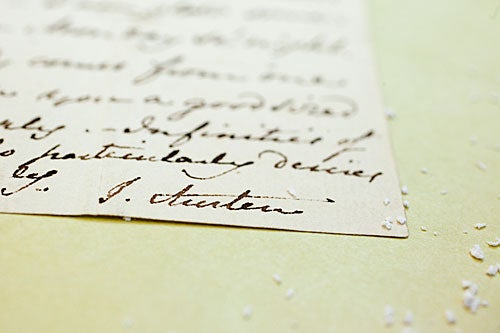

Sincerely

Austen’s signature appears at the bottom of this 1813 letter.