At the first Harvard Thinks Green, six Harvard professors gathered at Sanders Theatre to provide just that kind of thinking. They included Eric Chivian (from right), Rebecca Henderson, Christoph Reinhart, Robert Kaplan, Richard Lazarus, and James McCarthy. Hosting the event were Office for Sustainability Director Heather Henriksen (far left at podium) and event co-founder Peter Davis ’12.

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Thinking green, and thinking big

Six faculty share transformative ideas for sustainability

A problem as complex and potentially intractable as climate change demands equally big solutions. At the first Harvard Thinks Green on Thursday, six Harvard professors gathered at Sanders Theatre to provide just that kind of thinking.

The event was meant to tap into the “original fundamental reason why we are all here on campus for four years: ideas,” said Peter Davis, a senior who co-founded Harvard Thinks Big, which co-sponsored the event with the Office for Sustainability and the Center for the Environment. At Harvard, students have the opportunity “to propose them and play around with them and fight against them and to sometimes even work to implement them.”

Their ideas, which touched on corners of society from science and medicine to politics and urban planning, made it clear that reversing the declining health of the environment can’t be left to any one group.

Don’t wait for Washington

In 2009, President Barack Obama used the words “global warming” or “global climate change” in 69 public appearances. In 2010, that number rose to 73. This year, Obama has mentioned climate change once. Clearly, argued Richard Lazarus, Howard and Katherine Aibel Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, climate change has become an untouchable cause in Washington.

After years of legislative inaction on climate change, “the United States is experiencing an environmental law-making crisis,” Lazarus said. But there’s no use in pointing fingers at politicians, big business, or other power players for the climate crisis. Rather, he said, the U.S. legal and political systems simply aren’t designed to address long-term, global problems. The Constitution limits sweeping legislation, and lawmakers aren’t rewarded for it at the polls.

To change the climate (no pun intended) in the capital, he recommended ending the filibuster, which empowers senators with short-term motives to reject climate change legislation, and promoting the work of individual states such as California that are experimenting with their environmental laws.

If anyone has the power to shake things up in Washington, it may be the military. “They care about real facts, real science, and real risks,” Lazarus said. As oil demand increases worldwide and as drought and famine ravage continents, the military must prepare for potential resource wars or mass migrations. “Occupy the military,” Lazarus suggested to the audience.

Change the dialogue

“We must help educate people about what’s really happening to the environment in language that they can relate to and understand,” said Eric Chivian, director of the Center for Health & the Global Environment and an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School (HMS). “There’s no more compelling way to do this than to talk about human health.”

Chivian should know. In 1985, he won the Nobel Peace Prize for his work with International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, a group he co-founded in 1980 to convince the public of nuclear war’s potential human toll. The same kind of practical, health-oriented outreach can and should be done to mitigate climate change, he argued.

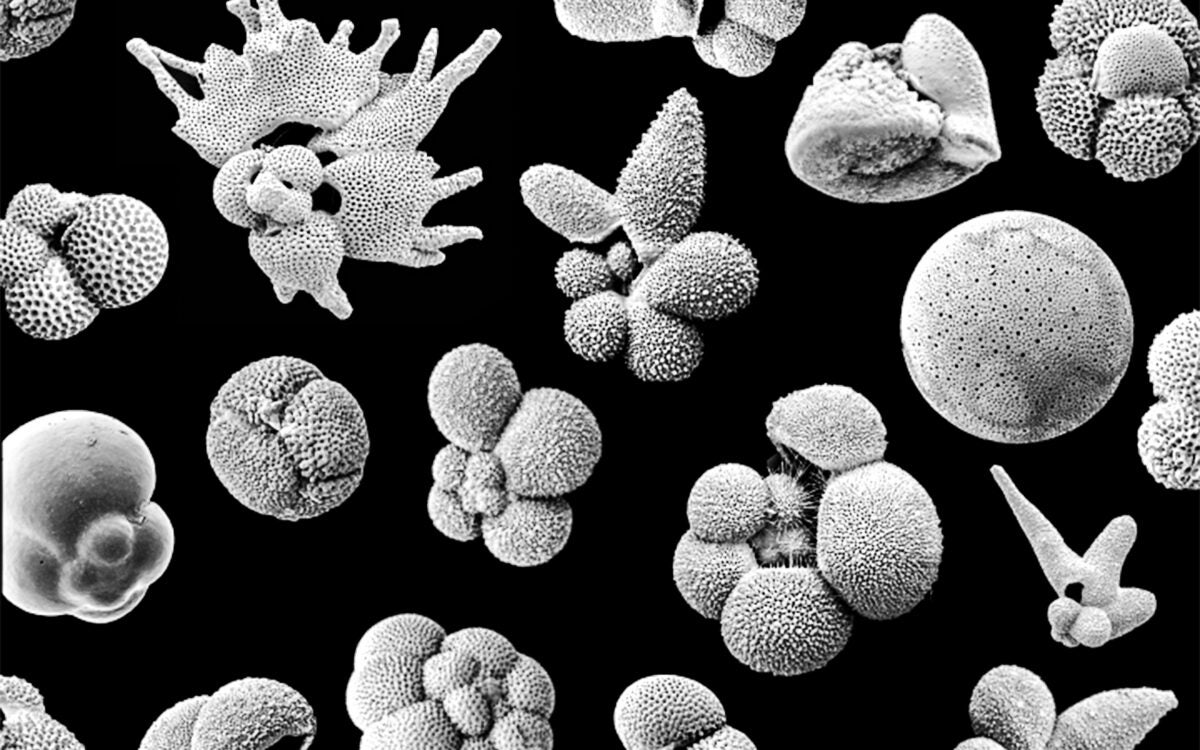

“Global climate changes can be very hard to see,” he said, and “we have no Hiroshimas or Nagasakis to serve as models.” But the loss of biodiversity, for example, could have great costs for medicine. For instance, if polar bears become extinct by 2100 as predicted, scientists will never unlock the mysteries of their hibernation — why don’t polar bears lose bone mass when they’re immobile for six months at a time? — that could hold beneficial knowledge for suffers of osteoporosis.

Medicine also provides useful metaphors for why people must act now against climate change. When treating an infant for a fever, for example, “one doesn’t wait until the cultures come back two days later before starting [antibiotic] treatment,” he said. Although the vast majority of fevers are not caused by bacterial infections, the risk is too great to ignore.

A doctor “can’t afford to wait,” Chivian said, and neither should leaders who must address climate change.

Look to business

At its best, business can improve the human condition by bringing technology to the masses; at its worst, it can inspire greed that leads to poverty, pollution, and other ills. But no one should doubt that business will be a powerful ally in the fight against climate change, said Rebecca Henderson, John and Natty McArthur University Professor at Harvard Business School (HBS).

“In the long run, there is no better hope for human progress than business,” she said, “because business is about innovation and scale. Business has learned how to motivate people in ways we’ve never seen before.”

After spending 20 years studying large companies undergoing dramatic shifts, Henderson said, she knows that big changes — for example, committing to reducing emissions from factories or investing heavily in the development of new, noncarbon energy sources — will be painful for the industries that undertake them. But if Americans can restructure the ways we do business to place more value on long-term results, the payoffs of combatting climate change could be huge.

“Building an enterprise that opens a whole new market, getting really rich, and making a difference … is a high like almost no other high,” she said. “This transition we face as an economy, as a world, is ripe for the taking. It is going to hit every major industry: agriculture, energy, construction, consumer goods, textiles, services.

“It’s coming down the pike. It can make us all rich,” she continued. “But it will require commitment, vision, hard-headed realism, and the creativity to unite those to make it happen.”

Target cities, building by building

Buildings are an often overlooked culprit in global warming, said Christoph Reinhart, associate professor of architectural technology at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD). They account for 40 percent of carbon dioxide emissions, and unlike other climate offenders — say, gas-guzzling old cars — most won’t be replaced by new state-of-the-art structures anytime soon.

“One can make mistakes but should not build them,” he mused, quoting Goethe.

What we can do, Reinhart insisted, is empower architects and urban planners to develop sustainable neighborhoods by giving them more sophisticated tools for measuring buildings’ impacts on the environment.

Working with one of his GSD classes, Reinhart has already designed a model that combines predicted climate changes with future price scenarios to show what a building is likely to cost its owner over the years in energy bills. Such models make the effects of climate change measurable, and can help to justify the cost of energy-efficient upgrades to old buildings.

“Working on the design, construction, and maintenance of energy-efficient and comfortable cities is a defining task of our time,” he said.

Leaders wanted

Tackling climate change will require true leaders — people with strong convictions and the courage to act on them, said Robert Kaplan, an HBS professor of management practice.

For a good example of strong leadership on sustainability, Kaplan looked not to Washington or the global community but to Harvard itself. The University’s 2008 plan to model sustainability through both research and campus activities — and its specific goal of reducing Harvard’s carbon emissions by 30 percent over a decade — “was and is an ambitious goal.” By creating specific priorities and action plans, and by bringing Harvard’s disparate Schools together in the process, Harvard is well on its way to achieving its reduction target under President Drew Faust’s watch, he said.

“A lot of people think leadership is about charisma,” Kaplan said. “But we’re learning here at Harvard through sustainability that it’s about articulating a clear vision,” creating a detailed plan, and following through on the specifics. “Just think if we followed this template in our government,” he added.

Think small, too

2010 saw the single largest jump in carbon dioxide emissions worldwide (5.9 percent) of any year on record, according to figures released earlier this month by the Global Carbon Project. Thanks to rapid industrialization in China and India (and increasing demand for those countries’ products in the United States and Europe), it’s more pertinent than ever that we change our ways, said James McCarthy, Alexander Agassiz Professor of Biological Oceanography.

“The later we start this, the more difficult it will be,” he said.

The good news is that introducing a host of small, “painless” changes to the way people use energy can make a marked difference, McCarthy said. He cited Harvard and the city of Boston, which hopes to reduce the city’s greenhouse gas emissions by 25 percent by 2020. Both organizations have identified many small areas for improvement that add up to a larger environmental goal.

“By the time you leave in four years, you will have seen real progress,” McCarthy told students in the audience. “Those small differences really do add up.”

[gz_video youtube_id=”EE1PaFncoOA”][/gz_video]