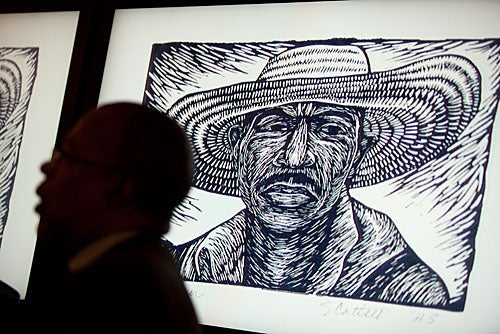

“DIGAME: Elizabeth Catlett’s Forever Love” features work by 96-year-old artist Elizabeth Catlett, including the color linocut “Sharecropper” (above, detail) from the 1950s. The exhibit is on view in the Du Bois Institute’s Rudenstine Gallery through May 26.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Principled expression

Elizabeth Catlett, 96, reflects on art, activism

In the intimate gallery at Harvard’s W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research, a powerful new exhibition offers viewers a sense of despair, and hope.

“DIGAME: Elizabeth Catlett’s Forever Love” features work by 96-year-old artist Elizabeth Catlett. The show is on view in the Rudenstine Gallery through May 26.

Many of the images portray African-American women and men caught in a world of racial, social, and economic injustice. A linocut from Catlett’s “The Black Woman” series created in 1946 and 1947 depicts African Americans riding in a bus behind a “colored only” sign. The piece is titled “I Have Special Reservations.”

But in what might be the exhibition’s most iconic work, “Sharecropper,” a female farmer, her face worn by the elements and years of toil, carries an expression that has been described as both “determined and commanding.”

A sculptor and graphic artist, Catlett was born in Washington, D.C., in 1915. She is best known for her politically charged black expressionist sculptures and prints. Her activism led to her arrest in 1958 while protesting the Union of Railroad Workers’ strike in Mexico City. Four years later the State Department declared her an “undesirable alien.”

Catlett studied painting at Howard University, graduating in 1935. In 1940 she became the first African-American student to receive an M.F.A. in sculpture from the University of Iowa. She relocated to Mexico in 1945 upon receiving a grant from the Rosenwald Foundation. There she worked closely with the People’s Graphic Arts Workshop, a group of artists dedicated to using their talent to promote social change. Her peers included famed artist Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo.

Catlett became a Mexican citizen in 1959. She joined the faculty of the National School of Fine Arts at the National Autonomous University of Mexico as a professor of sculpture and eventually became the first woman to head its sculpture department. She retired from the institution in 1976.

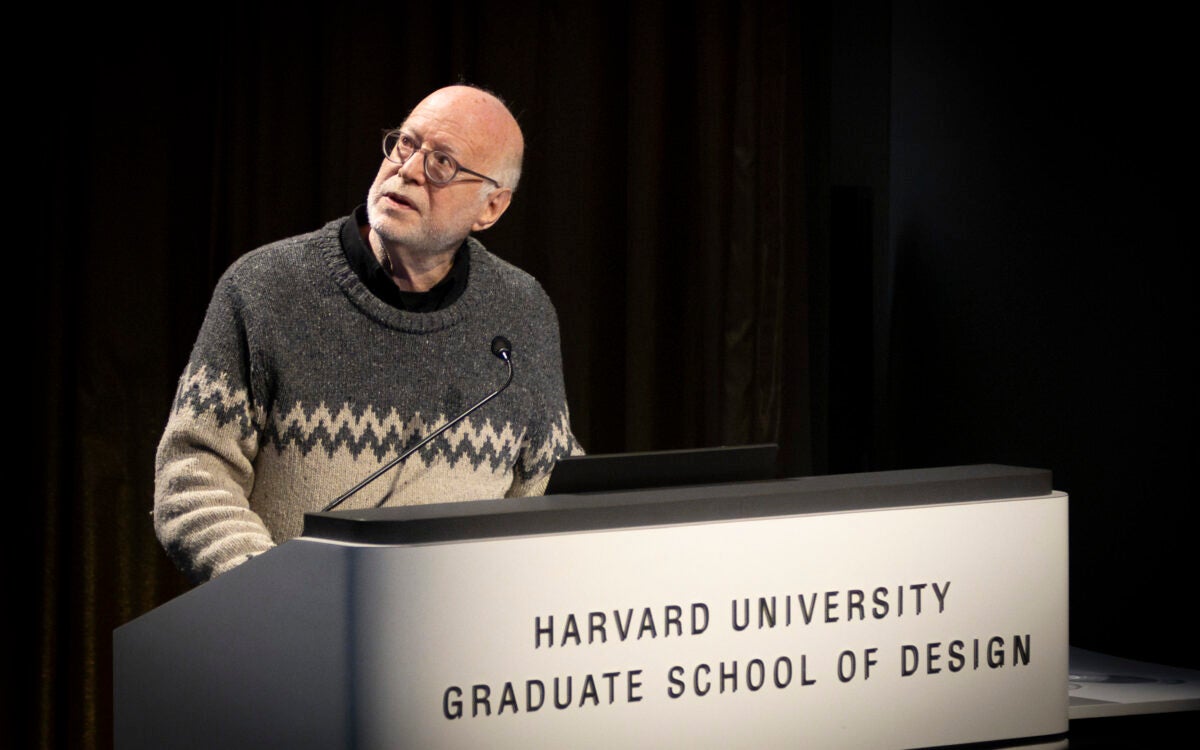

A grandchild of slaves, Catlett, who recently turned 96, spoke at Harvard on April 18 at the center’s Hiphop Archive.

Her experience with race in America has informed her work, she told Henry Louis Gates Jr., the institute’s director and Alphonse Fletcher University Professor.

Asked by Gates why the image of the sharecropper has featured prominently in her work, Catlett described the farm near her grandmother’s house in North Carolina, where she spent her summers as a child.

“I met these people and played with their children and they left a big impression on me,” said the artist. She also recalled how the owner of the land would “run his hounds” through the fully grown corn and cotton, ruining their crops.

“They had no respect for anything.”

When Gates asked Catlett why she decided to become a Mexican citizen, she said that in Mexico, “I was just a woman; I didn’t have to be a black woman.”

Time hasn’t stopped Catlett, who is still at work on her craft. She recently completed a 10-foot sculpture of gospel legend Mahalia Jackson for New Orleans’ Treme neighborhood.

Share this article