Conevery Bolton Valencius, a lecturer on the History of Science, teaches a course on American environmental history, from the clash of European and Native American models to slave-based agriculture to current debates.

Justin Ide/Harvard Staff Photographer

America’s Eden that wasn’t

Rivers and land helped to shape nation’s environmental history

In the summer of 1844, author Nathaniel Hawthorne set out into the woods around Concord, Mass., to record his impressions of nature. But his reverie was soon interrupted by the shriek of a locomotive. It was a sound, he wrote, “harsh above all other harshness.”

Moments of similar intrusion are common in American literature, the sudden imposition on a pastoral scene of what critic Leo Marx called “the machine in the garden.” Henry David Thoreau recorded similar moments, as did Mark Twain, Faulkner, Hemingway, Steinbeck, and other writers mourning the loss of an American Eden. In its place, Thoreau wrote in disgust, was the “maimed and imperfect nature” of modern life.

But wait, a new Harvard College course asks: Was there ever an American Eden?

“We read too much Thoreau,” said Conevery Bolton Valencius, a lecturer in history of science. “Them’s fighting words for someone teaching environmental history.” But this semester she’s ready to reveal the past as it actually was in History of Science 132: “This Land Is Your Land: A Survey of American Environmental History,” the department’s first course in the history of the American environment.

In the syllabus, Thoreau appears “as a kind of interloper,” said Valencius, as an aberration in a 19th century nation in which nearly everyone else “sees natural resources as something to be used fiercely.”

In fact, she said, people in Thoreau’s time were more likely to read James Fenimore Cooper, the novelist who so mildly noted the mass killing of passenger pigeons.

“People have used nature all throughout, and before, American history,” said Valencius, who earned her history of science Ph.D. at Harvard in 1998. “We moderns forget that.”

Her fast-paced survey is designed to awaken students to America’s past as a place of ascendant farmers and loggers and land-hungry pioneers. Even the Native Americans had altered the natural world around them, clearing forest tracts by fire to plant corn and beans.

“The past is a different country,” said Valencius. “The environments we live in are not the environments of the past.”

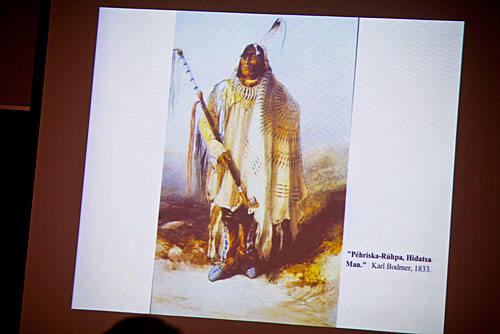

It takes some guidance to get back to that environmental past, and her animated lectures help. In a spacious seminar room in the Science Center, where 20 students from diverse concentrations listened in, Valencius illustrated her points with maps, paintings, and lithographs. She played snatches of song, read from contemporary journals, and — with a little prompting — even mimed what it took to pull a barge along a canal.

From the course pack, students read about the “corn chiefdoms” of early America, Osage land use, the ecology of colonial New England, and the imposition of “Jefferson’s grid,” a system of lines on a map that express ownership from a distance. (It was an alien idea to American Indians, who drew maps as a series of circles that were never expressions of property.)

They read from the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-06), the party of explorers in six canoes and two flatboats that Meriwether Lewis grandly compared to the brave fleets of Columbus and Capt. James Cook. “The United States finds itself, somewhat surprised, in possession of another third of the continent,” said Valencius of that pivotal exploration. “It was not at all clear what had been bought.”

The course races along a timeline marked by other resonant dates. The Land Ordinance of 1785 expressed the central role of the first federal government, said Valencius, to distribute land, and to counter earlier British attempts to limit westward migration.

In 1862 came the Homestead Act, setting the stage for independent farmers to, among other things, upstage the model of Southern enterprises dependent on slavery.

In the period 1900-30, the population of Los Angeles boomed from 100,000 to 1 million. It was a sign that the center of U.S. gravity was shifting to the West, where vast mineral resources awaited fervent extraction.

In the mid-1930s, America busily harnessed virtually all of its rivers for power. Today there are only a few undammed rivers, including the short (150-mile) Buffalo River in Arkansas, where Valencius grew up. (In the course, rivers are a main actor, as America’s oldest transportation routes, as well as its political fracture points.)

Then came 1945, when the first atomic bomb was dropped, and overnight, said Valencius, came “the recognition that we could destroy vast swaths” of the natural world.

In 1962, when the book “Silent Spring” was published, “Americans began to fear their own domestic environments,” she said, and felt a widening unease at the idea that nature was there to be conquered.

By 1970, with the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act, the regulatory machinery was in place to temper the environmental costs of modern life. But then came a counterpoint year, 1980, when Ronald Reagan — “the sunshine president from the Sunshine State,” said Valencius — brought with him a new skepticism about federal intervention in environmental issues.

In 2006, the film “An Inconvenient Truth” helped to set off the latest major environmental dispute. Overnight, climate change was being debated even in small-town newspapers, said Valencius, and ordinary citizens were “armed” with facts on a complex issue.

The year 2006 “is not viewed as a marker yet in the history of science,” she said, but it will be.