Determined to work on his public speaking skills, Shao-Liang Zheng sought the help of the Crimson Toastmasters, a campus chapter that helps Harvard faculty and staff to overcome the nerves, tics, and other barriers to communication that can plague even seasoned public speakers. “It’s given me the confidence, and it helps me with organization of my thoughts,” Zheng said.

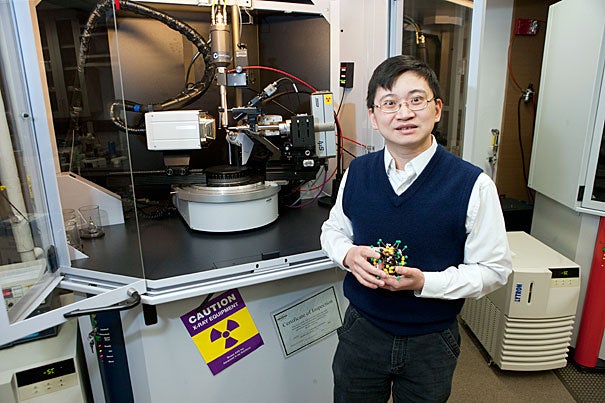

Brooks Canaday/Harvard Staff Photographer

Losing the ‘likes’ and ‘ums’ but finding a community

Crimson Toastmasters builds confidence and camaraderie

Shao-Liang Zheng can manipulate the tiniest of molecules, but he has a harder time manipulating words.

Zheng, who manages the Center for Crystallographic Studies in the Chemistry and Chemical Biology Department, is by his own admission “a little shy.” And his pronounced Chinese accent often makes for unwieldy conversation with Americans. The communication problems Zheng could frequently avoid as an isolated postdoctoral researcher came to the fore when he began teaching others how to use the center’s complex X-ray machinery.

“The first time I ran the workshop here, students complained they couldn’t understand me,” he said.

Determined to work on his public speaking skills, Zheng sought the help of the masters — specifically, the Crimson Toastmasters. The four-year-old chapter meets every other Tuesday afternoon with the goal of helping Harvard faculty and staff to overcome the nerves, tics, and other barriers to communication that can plague even seasoned public speakers.

“It’s given me the confidence, and it helps me with organization of my thoughts,” Zheng said.

Most people have heard of Toastmasters International, the nonprofit public-speaking organization founded in 1924. With its 10-step path to “competent communication” and its members-only mystique, Toastmasters has acquired a reputation as a cross between Alcoholics Anonymous and Six Sigma, the popular business methodology.

“I actually thought it was a cult,” admitted Sarah Liberman, a coordinator in the Harvard Graduate School of Education’s academic affairs office. Despite her skepticism, she attended the club’s inaugural meeting, sponsored by the Center for Workplace Development, and is now its vice president for membership. “It’s a really good opportunity to network,” Liberman said.

For some, Toastmasters conjures an image of a fusty old man in a dinner jacket and ascot, raising a coupe of champagne to commandeer the room’s attention.

“I thought that it might be more formal than it is, maybe more elitist,” said Christie Gilliland, a newer member of the club and a Harvard Library assistant. “But it was the exact opposite.” Even though Gilliland is naturally outgoing, she said she likes the regular practice that Toastmasters provides.

“You have to learn how to work through the racing heart, keep your mind focused even when your hands are shaking,” Gilliland said.

The oft-quoted statistic that more Americans fear public speaking than death — the common belief that, as Jerry Seinfeld famously joked, “If you go to a funeral, you’re better off in the casket than doing the eulogy” — appears to be the stuff of urban legend. But a 2001 Gallup survey did reveal that public speaking is the second-most-common fear in America, after snakes.

And even those who don’t dread the spotlight aren’t necessarily good at handling it.

“I come across a lot of people who are professionals at a really high level who can’t give a good presentation,” said Leon Welch, a purchasing assistant at Harvard University Health Services and the club’s president.

Toastmasters is everywhere. There are 164 clubs in Massachusetts alone, many affiliated with universities, businesses, or churches. Harvard students have their own Toastmasters club, Harvard Toastmasters, which meets weekly at the Harvard Kennedy School.

All Toastmasters clubs follow the same meeting format, where members take turns being master of ceremonies and giving speeches that range from an opening joke to an inspirational thought. Some members are assigned to offer critiques — and yes, one person tallies all the “ums,” “likes,” and “sos.” But any Toastmaster will insist that clubs have their own personalities, from the militant to the relaxed.

“What sets our group apart is a tremendous amount of compassion and understanding,” Welch said. “We have one of the most amicable groups I know of.”

Welcoming or not, a room full of strangers can seem like a hostile environment to a newcomer, especially one who fears public speaking. Even though no one is required to take a turn in front of the group, “We’ve had people cry,” Welch said.

Crimson Toastmasters is small but growing, Welch said. Many members discover the club by word of mouth. “A lot of people are looking to become more proficient in the way they present themselves,” he said. “I think that the Toastmasters approach is attractive, because you move at your own pace.”

Jason Pryde, a web and database manager at the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, said the group has helped his professional life in unexpected ways. He has gotten better at recognizing people and remembering their names. And he has become attuned to the reciprocal aspect of public speaking: listening.

“It’s fairly easy to let your mind wander off when people are speaking,” Pryde said. “But it’s dangerous. I’ve disciplined myself to stay engaged.”

In uncertain times, people often look for ways to bolster their public speaking skills to gain a competitive edge in the work force, said Steven Cohen, author of the recently released “Lessons from the Podium: Public Speaking as a Leadership Art.” Cohen, a Harvard Kennedy School graduate who teaches a course on public speaking at the Harvard Extension School, said he has seen a spike in interest in public speaking across the University in recent years. In the five semesters he has taught the class, it has filled up in a matter of days, with a waitlist.

“Especially with the economic downturn, people are doing whatever they can to stay on top,” said Cohen. “Public speaking is one of those areas that can make or break you.”

It’s certainly had a real impact for Zheng and the Center for Crystallographic Studies. When Zheng arrived at Harvard in 2009, only eight students and postdoctoral researchers knew how to use the X-ray equipment he oversees. Thanks to his training workshops, that number now stands at 22, not counting the 7 new students currently taking a new course Zheng is teaching.

“It makes me so happy,” Zheng said with a grin. “It’s very hard to stand up and speak, but it’s important for my job. It’s important for the students.”