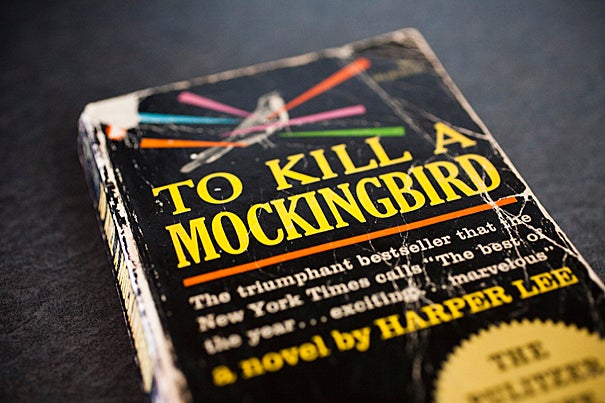

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘Mockingbird’ memories

An iconic Southern novel turns 50

On July 11, 1960 — 50 years ago this weekend — the novel “To Kill a Mockingbird” appeared in bookstores for the first time.

In the decades since, author Harper Lee’s iconic novel of race, class, courage, gender, and moral complexity has never been out of print. The instant classic went on to be published around the world in more than 5,000 editions.

What has made the story of Atticus Finch, Scout, Jem, Dill, and the doomed Tom Robinson so durable? A few Harvard professors weighed in on the novel, set in sleepy Maycomb, Ala., in the 1930s. The people moved slowly, Lee wrote, grass grew in the sidewalks, and “men’s stiff collars wilted by nine in the morning.”

But fictional little Maycomb was also a place where racial tension simmered like summer heat — a place that Lee invented just as the American Civil Rights movement flowered. “To Kill a Mockingbird” — which soon won a Pulitzer Prize and was made into an Oscar-winning film — became the bestseller that summed up the moral quandaries of a race-charged age.

“It was a landmark book,” said Vicki A. Jacobs, associate director of the Teacher Education Program at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. “The themes are universal, despite time.”

One of those themes is self-realization, she said, the journey to moral and social awareness that Jem and Scout make as children confronted with the tragic consequences of Maycomb’s fragile racial climate.

“ ‘Lord of the Rings’ endures, Shakespeare endures,” said Jacobs, a specialist in literacy, curriculum, and the teaching of English. “It’s all about a basic struggle.”

“To Kill a Mockingbird” was one of the first novels in a new canon of books that represented a diversity of voices, and that children gladly read, she said. It still resonates today at least as a social document from a time when Americans struggled as a nation with the moral dilemma of race relations. “I’m more interested in it as a piece of history,” said Jacobs. “It’s more of a book I carry emotionally.”

In the book, much to the surprise of his children Jem and Scout, the mild and quiet Atticus shoulders a rifle, and expertly shoots down a mad dog roaming the streets of Maycomb. In the courtroom later — defending Robinson from trumped-up rape charges — Atticus takes aim at what critics have called the “mad dog” of racial prejudice.

But it’s not such an easy shot. Robinson, one of the innocent “mockingbirds” of the title, is convicted despite porous evidence, and is eventually shot dead while trying to escape. He’s the victim of racism’s mad dog.

“Those are twelve reasonable men in everyday life, Tom’s jury,” Atticus said later, “but you saw something come between them and reason. … There’s something in our world that makes men lose their heads — they couldn’t be fair if they tried.”

James Simpson, Harvard College Professor and Donald P. and Katherine B. Loker Professor of English, grew up in Australia. But in his childhood, “To Kill a Mockingbird” still made itself felt on the other side of a great geographic and cultural divide.

“Even way down there in Melbourne, the book cast its potent spell over generations of schoolchildren,” said Simpson, who also chairs the English Department, “evoking and half calming their anxieties about that spooky, silent house on the corner that every child fears.”

The book also delivered a very American message. “ ‘Catcher in the Rye’ brought America to Melbourne adolescents by a mesmerizing voice,” said Simpson. “But ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ brought America to Melbourne through something much deeper — a palpable atmosphere of dark and troubling pasts, all unlike anything we knew.”

Lee’s classic was not life-changing to Walter Johnson, Winthrop Professor of History at Harvard, and a professor of African and African-American studies. For that power, he prefers Anne Moody’s “Coming of Age in Mississippi.” The 1968 memoir follows a black woman through the humiliation of the Jim Crow era and the turbulence of the civil rights struggle.

As for “To Kill a Mockingbird,” “its moral center resides in a white male redeemer,” said Johnson, who studies 19th century American slavery, capitalism, and imperialism. “That might account for some of its popularity and longevity, [but] it also defines and — to an extent — limits its moral and ethical vision.”

Like the movie “Amistad,” the novel’s moral focus seems racially one-sided, he said. “Both the strength and the weakness of the book is that it is, in the end, a book about white people.”

Will its rugged popularity in the classroom last? “To Kill a Mockingbird” may not always be a feature in that canon of books still taught in high schools and middle schools, said Jacobs. But for now, “it still has its place,” she said, and her students regularly choose it when teaching their English classes.

Simpson had greater hopes for Lee’s classic. “May books like this one,” he said, “continue to live much longer.”