Devastation by degrees

‘What global warming means is that [Massachusetts] just moved to North Carolina’

In the past two decades, more than 20 percent of the polar ice caps have melted, parts of Greenland are fast disappearing, and the world’s oceans are increasingly acidic, threatening the life they sustain both in their waters and on their shores.

The evidence is mounting that the world is warming at alarming rates, but a pending climate conference in Copenhagen next month, aimed at curbing the planet’s carbon emissions, is in danger of failing before it begins.

Closer to home the climate change implications are equally bleak.

“What global warming means is that [Massachusetts] just moved to North Carolina,’’ said Peter Lehner, executive director of the Natural Resources Defense Council. “It’s a pretty significant change in what it’s going to be like around here.”

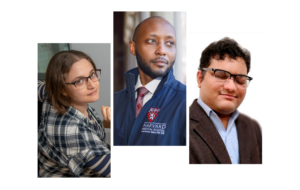

Lehner, executive director of the Natural Resources Defense Council, delivered that grim message during a discussion this week (Nov. 2) that was part of the Harvard University Center for the Environment’s Green Conversations series.

Lehner took part in a session with Daniel Schrag, director of Harvard’s Center for the Environment and professor of earth and planetary sciences and professor of environmental science and engineering, and Joel Schwartz, professor of environmental epidemiology and associate professor of medicine at the Harvard School of Public Health.

“There’s no question the world is going to survive. The question is: Will human civilization as we know it survive?” said Lehner.

But the news isn’t only bad. Lehner, whose nonprofit group is a major player on the nation’s environmental-advocacy stage, outlined a plan to curb global warming that includes government involvement as well as effective climate policies that mitigate costs and support new, cleaner technology.

There is no “silver bullet” to the global warming crisis, said the executive director. The solutions involve better energy efficiency, cleaner fuel, better public transportation options, and increased use of wind and solar power. Limiting the use of carbon and making those who do it pay for an emissions allowance are also essential, he said.

Another critical step involves the American Clean Energy and Security Act, which was approved by the U.S. House in June. But getting the bill through the Senate is likely to require 60 votes and a delicate balance of policy and politics, said Lehner, since many senators worry that new energy-efficiency policies will hurt industries in their home states.

“We need to take their concerns seriously and devise a bill that both achieves our environmental goals but also addresses these concerns,” he noted.

One such compromise would involve coal, which is currently responsible for half of the nation’s electrical supply and is a major factor in producing greenhouse gases. Carbon sequestration is a process that buries carbon pollution from coal deep underground instead of releasing it into the atmosphere. The technique meshes with new climate legislation, said Lehner, since it allows coal usage in a way that “won’t necessarily fry the planet.”

Getting the bill through Congress before the climate meeting in Denmark next month will be an uphill battle, admitted Lehner.

“Whether or not we will do it in time for Copenhagen, who knows? But hopefully we will do it in time to make a difference for all of you.”

Lehner also answered critics who complain that China, a developing nation that is now the biggest producer of carbon emissions, has a responsibility to act ahead of the United States to stop climate change. Using a graph, he showed per-capita data revealing that the United States is still far ahead in terms of its own carbon emissions.

He added that carbon dioxide lasts in the atmosphere for about a century.

“Much of what’s up there is ours — it’s not China’s — so the effects that are already being caused are from the Western world, and from the United States.

“It’s going to be a new energy world for the entire planet,” he added, “and, if it’s not, we are going to be in trouble.”