Glimchers are unusual father-daughter duo

HMS, HSPH professors collaborate on bone-immunology linkage

Laurie Glimcher remembers going into her father’s laboratory at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) as a child, seeing beakers full of liquids being stirred automatically, and wondering not just what was in them, but what her father would learn from them.

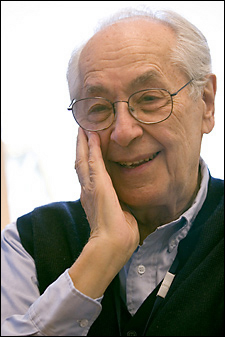

Her father, Melvin Glimcher, who chaired MGH’s Orthopedics Department at the time, nourished not only bone cells in that lab, but also his middle daughter’s passion for science.

Today, Laurie and Melvin Glimcher are something of a rarity at Harvard: a father-daughter pair who both hold named chairs in their respective fields and who carry on a fruitful collaboration that is illuminating the intersection of immunology and osteology – the study of bones – in an emerging field called osteo-immunology.

Most recently, the pair collaborated on research that led to the discovery of a mechanism that regulates bone growth. The findings, reported in the May 26 issue of the journal Science, may have provided a target for drug development to help people with osteoporosis, a danger for half of those over age 50.

That collaboration, conducted with several other authors, is the latest of a half-dozen or so papers in which father and daughter contributed, going back more than a decade.

Laurie, the Irene Heinz Given Professor of Immunology at the Harvard School of Public Health and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, has been the instigator of their collaborations, pushing her immunology studies to immune cells’ roots, which lie in the bone marrow, and then tapping Melvin’s expertise in that area.

Melvin, the Harriet M. Peabody Professor of Orthopedic Surgery at Harvard Medical School and director of Children’s Hospital’s Laboratory of Skeletal Disorders and Rehabilitation, has always been willing to help and stands ready to offer an insight or a wry joke, whichever is needed.

While the two have been successful together, each has also become prominent in their fields independently. Both are members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and have received numerous awards. Laurie is also a member of the National Academy of Sciences. They have been widely published – more than 200 articles each – and several patents have resulted from their individual work.

“They both are major leaders in their respective fields. They certainly both have reputations for intensity and brilliance, but also for nurturing young scientists,” said Professor of Medicine Henry Kronenberg, at Massachusetts General Hospital, who has worked with both Glimchers.

Kronenberg said he experienced that nurturing side firsthand, as Melvin took an interest in his work soon after he arrived in Boston 25 years ago.

“He was very supportive of my research. Just having someone of that stature expressing interest and even enthusiasm is tremendously helpful early in a career,” Kronenberg said.

Laurie grew up in the Glimcher home in Brookline with her sisters Susan and Nancy – both tax attorneys today – Melvin, and her mother, Gerry.

Melvin was busy, but he found time to bring Laurie to work with him when he could. She was the only one of his three daughters who showed an interest in science and he was determined to nourish that interest.

The nourishing, however, had its ups and downs. There was the disastrous crayfish experiment when she was in grade school – the crayfish escaped and crawled all over the kitchen; and the chicken-hatching experiment a few years later – banished to the garage by Gerry.

As she grew older, the encouragement grew and Laurie remembers working in Melvin’s lab over the summer when she was an undergraduate at Radcliffe College. In a sign of things to come, Laurie did her senior thesis on bone cells, showing that one type, an osteoclast, derives from an immune cell called a macrophage.

“We’re full circle after 40 years,” she said recently. “Back to the macrophage turning into the osteoclast.”

Melvin said he had a few nervous moments when Laurie was at Radcliffe, as she headed to Europe one summer to pursue an interest in acting. He breathed a sigh of relief, he said, when she called from Italy and said she had decided to go to medical school after all.

As her father did, Laurie graduated from Harvard Medical School, winning the Soma Weiss Prize for medical student research exactly 26 years after her father won the same award. Melvin, who was sitting in the back of the auditorium, was thrilled, and remembers running down the steps and hugging her, despite her protestations.

“I zoomed down to the bottom and gave her a hug. She said, ‘Stop it, stop it,’ But I said, ‘It’s all right.’ She was a little embarrassed,” Melvin said.

Later, when Laurie was standing on her own feet professionally, but struggling to balance the demands of work and the needs of two young children, Melvin and Gerry were there to support her.

Laurie recalls in particular the years when she was doing a full-time clinical rheumatology fellowship and setting up her lab. She had two small children, one 6 months and one 3 years, and her husband, Hugh Auchincloss, from whom she is now divorced, was a surgical resident and at the hospital for much of the time.

“I would not have survived that without my parents,” Laurie said. “They were five minutes away. I remember when Hugh would go in Saturday morning. I knew we’d see him next on Monday evening. I’d pack up the kids and basically move into my parents’ house for the weekend. I’d go into the lab and he [Melvin] would take them to the playground. He must have come over two or three times during the week in the evening to take them out.”

For his part, Melvin acknowledges that, given the demands of his own career when he was in that same, crazy stage, he was able to be around more for his grandchildren than his children. He’d swoop in and take them home for dinner.

“I was the fastest diaperer in the East,” Melvin said.

Today, both Laurie and Melvin take a particular delight in the decision of one of Laurie’s sons, Hugh, to follow them into Harvard Medical School. Though Hugh is now a third-year medical student, both Laurie and Melvin were there when he arrived at Vanderbilt Hall for his first day, much as they had, 32 and 50 years earlier.

When asked how it felt looking down the generations at his daughter and now his grandson as they entered the same field, at the same institution, Melvin said it’s difficult to describe.

“You can’t imagine. It’s worth …” he said, pausing as if searching for the right word. “Everything.”

Related links:

Share this article

- Researchers discover mechanism that regulates bone growth: Pathway promising for osteoporosis treatment

- U.S. awards School of Public Health $20.5 million grant: Largest grant ever given to HSPH for biodefense research

- Harvard Researchers Find Genetic Key to T Cell Differentiation