When is a philosopher not a philosopher?

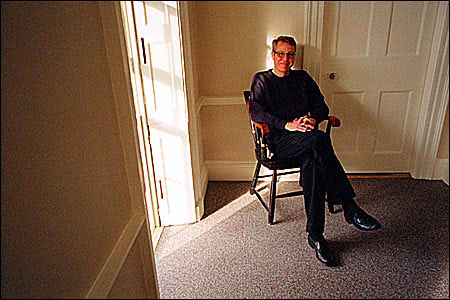

When he’s film scholar David Rodowick

“Philosopher.”

It’s the first descriptive word on David Rodowick’s Harvard Web page, coming immediately after his name and before “Professor of Visual and Environmental Studies.”

Yet Rodowick, who joined the Harvard faculty at the beginning of this academic year, admits that he’s not technically a philosopher: His Ph.D. is in communication and theater arts, his teaching career has been in departments of film studies as well as literature, English, and cultural studies.

Describing his work, however, Rodowick makes it plain that his engagement with the study of film is, first and foremost, a philosophical one.

“One large question that I always come back to is this interest in the way in which film, and various time-based media, seem to very deeply inform what contemporary culture is about … the ways that we think, evaluate ourselves morally, get information about our culture, deal with our culture aesthetically and perceptually,” he says. “Film is our unconscious, as it were.”

He describes the most recent of his four books, “Reading the Figural, or Philosophy after the New Media” (Duke University Press, 2001), as a philosopher’s book, one based more in the conceptual than in analyses of individual films. In it, Rodowick explores philosophy’s bias toward the notion that thought is concerned only with linguistic expression.

“What does that mean if you live in an … extremely sophisticated visual culture? What is the relationship between the visual and the spoken?” he asks. Film, as well as video and television, are forms that mix visual and spoken expression. In “Reading the Figural,” Rodowick proposes going beyond philosophy’s narrow linguistic underpinnings to understand how film, video, and even television are artistic as well as communicative media.

“They are the gateways through which, at least in developed countries, we understand our culture,” he says.

Film studies in the 21st century

Rodowick is currently at work on two books unified by the theme of “What will it mean to do film studies in the 21st century?” Born in the 1960s and ’70s, film studies is now a well-established discipline. “Yet just as it’s established, the whole field seems to be re-examining itself,” he says.

The first of the two books, called “The Virtual Life of Film,” explores what Rodowick calls a “sea change” in the history of film theory. Since the 1980s, almost every aspect of the technology of filmmaking – a photographic medium for nearly 100 years – has been replaced by digital technology. “What are the aesthetic as well as cultural consequences of the medium of film as it becomes something else?” he asks. And do they matter?

In the first part of the book, he argues on the one hand that it doesn’t matter at all – movies are movies and engage us in a narrative as they have since 1915. But the second part proposes that it matters enormously as film shifts from a photographic to a digital medium.

“The photographic seems to deal, no matter how fantastic the film, in a kind of documentary way with a certain time and place. It deals with physical things,” says Rodowick. Oz, while fanciful and wildly imaginative, was created by set builders.

Filmmaking has always been a balancing act between physical reality and the imagination, he says; the physical world had to be molded to the imagination. The digitized dinosaurs of 1993’s “Jurassic Park” tipped that balance. “The physical world is no longer a problem,” says Rodowick, who predicts that within 10 years, film will be an entirely digital experience. “It’s moving from a sculptural to a painterly medium.”

“An Elegy for Theory,” the second book, looks at the waxing and waning of theory in the study of film. Rodowick says the book’s central argument is that theory “is very important to both the background and the foreground of whatever we do in any field of study.”

Standing on the shoulders of giants

Although it’s not on his Web site or curriculum vitae, Rodowick also calls himself – only partly in jest – “the Johnny Appleseed of film studies programs.” Harvard, which launched a concentration in film studies this academic year, is the fourth university where he’s either started or rebuilt film studies programs, including those at Yale and King’s College London, his most recent appointment.

While he speculates that this unique administrative niche was at least partly responsible for his appointment to Harvard, he’s quick to note that film studies thrived here long before the concentration became official.

“Starting the film studies program was just signing the end of the document: Everything was already here,” he says, and has been for upwards of 30 years. He cites Stanley Cavell, the Walter M. Cabot Professor of Aesthetics and the General Theory of Value Emeritus and a leader in bringing together philosophical inquiry and film, and filmmaker Robert Gardner, associate of the Department of Visual and Environmental Studies, as the foundation of the University’s strong legacy of film studies. “We’re standing on the shoulders of giants,” he says.

Further, the rich resources of the Harvard Film Archive and the creative energy that already exists in filmmaking at the Carpenter Center have kept Harvard on the filmworld map – and made it a place Rodowick is excited to be a part of.

“My interest is in looking at film in the context of contemporary visual arts, and that is what the Carpenter Center does. It is a hotbed of experimentation and critical examination of contemporary and critical art and art practice. I felt intellectually and spiritually at home there. It seemed like the right place for me to pursue my own research interests, teaching interests, and maybe even artistic interests,” he says, referring to what he hopes is a rebirth of his earlier career in making films.

“I like to think that my coming here has been the last brick you tap into an edifice. Harvard is now a premier place for doing film studies, not just in North America but in the world,” he says. “It has a confluence of elements that cannot be rivaled anywhere. I think the institution can now take great pride in that.”