Chelsea, Mass.: A very special place

GSD class finds ways to show off the hidden treasures of the state’s smallest city

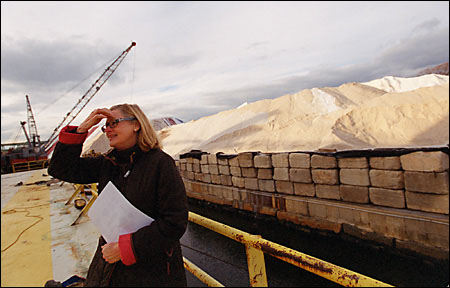

As the Boston Red Sox swept their way to a World Series victory this past October, innumerable messages of support began appearing all over the metropolitan area. There was one, however, that outshone the rest. Each night, the words “Go Sox” in letters 20 feet high, glowed on the side of Chelsea’s enormous salt pile, repository for all the highway salt in eastern Massachusetts.

Daniel Adams, a student at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD) came up with the idea for this monumental light show, which was executed with the help of Eastern Minerals, the pile’s owners, and lighting designer David Rudolph, a Chelsea resident. Adams followed it up with the message “Vote” around the time of the presidential election, and has plans for more projections.

But it is unlikely that any of this would have happened if Adams had not taken a GSD course with Margaret Crawford, professor of urban design and planning theory, called “Listening to the City.”

During the course, now in its second year, students design projects that address the city’s needs and aspirations – but only after a long process of research and exploration.

“Instead of telling the city what to do, which is the way urban planners typically operate, we decided to really listen,” Crawford said.

Crawford’s approach comes out of her work on the history and theory of the urban environment. Before coming to Harvard in 2000, she lived and worked for many years in Los Angeles, where she began taking a fresh look at parts of the city that more traditional urbanists either ignored or saw as problem areas. She began to see street vendors, unlicensed entrepreneurs, and other inhabitants of these poorer areas, not as disturbers of the social order, but as individuals creating their own public space in a process she called “reterritorialization.”

For her class “Listening to the City,” Crawford developed a methodology to enable students to put aside their preconceptions and open their eyes to the realities of the local urban environments. Chelsea seemed a good candidate for these investigations because it was easily accessible, densely populated, racially and ethnically diverse, and seemed to offer an intriguing complexity and vitality not immediately perceptible on the surface.

The students prepare for their forays into the city by reading a variety of texts ranging from theorists such as Michel deCerteau, Guy Debord, and Claude Levi-Strauss to fiction writers and poets like Italo Calvino, Virginia Woolf, and Charles Baudelaire. Through reading and discussion, they learn to assume a series of roles that put them in touch with the city in different ways, including the flaneur or strolling observer, the detective who searches beneath outward appearances, and the somnambulist who drifts through the city discovering its “psychogeography.”

But theorizing and observing are only the beginning. Through their investigations, the students get to know a wide variety of Chelsea residents including business people, government officials, and community leaders, and through these contacts they begin to understand the city’s needs and issues.

The class got a head start the first year thanks to Michelle Addington, associate professor of architecture at the GSD, who lives in Chelsea and was serving that year as a member of the city’s cultural council. Although the cultural council’s budget had been slashed to $9,000, the students, by working under the council’s umbrella and using the contacts Addington provided, were able to undertake a wide variety of projects that have had a significant and positive impact on the city. The city’s impact on these students has been profound as well.

“Chelsea is the smallest city in Massachusetts. It’s only 1.8 square miles. It’s like a microcosm of a large, complex city, but contained within a small area. It’s a really powerful place for students to be looking at,” Addington said.

In addition to Adams’ light shows, the first year of Crawford’s class has yielded a number of other efforts whose effects continue to be felt. Believing that aspects of Chelsea that make it unique and valuable were not apparent to the outside world, students got to work on a series of projects including creating shopping bags with a logo of the Tobin Bridge for local merchants; Chelsea postcards, notepads, T-shirts, and other souvenir items; a Chelsea Web page pulling together existing government and business Web sites with a cultural calendar; and a Chelsea restaurant guide. Other projects included a lighting installation commemorating Lewis Latimer, the African-American inventor and Chelsea resident who worked for Thomas Edison and made improvements to the light bulb; a planned public walkway for Chelsea’s working waterfront; and signage for Chelsea’s huge produce market.

Crawford stresses that the focus of the class is not to provide expertise to a city with economic and social problems nor to promote gentrification, but rather to enhance appreciation of the city’s assets and improve the quality of life. In the process, students gain an understanding of the city and what it takes to effect change.

“You can’t accomplish anything unless you partner with somebody in the community. It’s a good lesson for students,” Crawford said.

Adams, whose project never would have gotten off the ground without local support, agrees.

“I found that people were never too busy to talk, and they were always open to ideas,” he said.

This year the class has been working with the city planning commission and has come up with a number of projects including the reconfiguration of an abandoned mall, a series of scripts for Chelsea community television focusing on local businesses, and a plan to use signage and graphics to let people who park their cars in Logan Airport’s supplemental lot know that they are, in fact, in Chelsea.

According to Addington, the students’ involvement and their willingness to truly listen to the city and craft their suggestions accordingly creates an atmosphere of trust, which increases the likelihood that the city will listen as well.

“The class gave the city a new way of thinking about itself. It’s accepted now that Harvard will be part of the planning process in the future.”

Crawford agrees that the benefits of the class have been mutual.

“At the end of the class, there’s always a tremendous amount of student satisfaction. They get a lot out of it. And they all fall in love with Chelsea.”