Protein extends life

No dieting needed

For those of you who want to live longer, you’re getting closer to having your cake and eating it. You can even add a glass of wine.

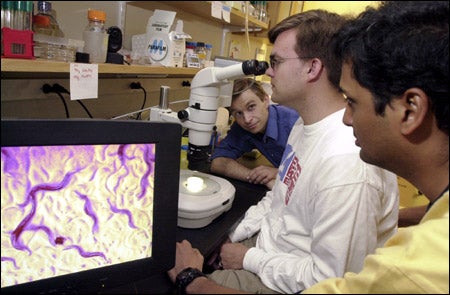

Last year, David Sinclair and his colleagues at Harvard Medical School extended the lives of yeast cells by feeding them a protein known as Sir2. This year, he fed a closely related protein to tiny worms and fruit flies. The worms lived as much as 14 percent longer, the flies as much as 23 percent. If it works in humans, that would extend our roughly 83-year lives to about 95 or 102.

The protein works on human cells growing in a test tube, but will it work on baby boomers trying to live the good life longer? “It’s pure speculation at this point, but we now have the first molecule that extends life in species, from fungi to flies,” Sinclair says. “If you arrange all the species on Earth on a scale of one to 10, yeast is a one, humans a 10, flies and worms are a nine. So we’ve come a long way.”

The protein molecule, in a form known as resveratrol, is sold by dozens of health-food companies. “About 10,000 people in this country take this product with no apparent side effects,” Sinclair notes. However, the pill has not been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration so people run an unknown risk by taking it.

Harvard Medical School rules prevent Sinclair from recommending the product, or admitting if he takes it. “However,” he says, “I know a number of scientists who think resveratrol is their best shot. Others satisfy themselves with a glass of red wine,” which contains the compound. (Fortunately, the extent of the effect does not depend on the price of the wine.)

Such compounds, known as STACs, activate the same natural proteins as severe calorie restriction, long known as a way to gain extra years. Reliable tests have shown that cutting calories extends the lives of yeast cells, worms, and flies. Now, Sinclair has shown these species can eat all they want and live longer with the help of STACs. The experiments he did with his colleagues are described in the July 14 issue of Nature.

Calorie restriction is embraced by a small group of people in this country who hope to have healthful (if not full) lives for 100 years or more by reducing their calorie intake by as much as 30 percent. A few of these people are also taking high doses of resveratrol. Of course, there is no way yet to know if it’s all going to be worth it.

Brian Delaney, president of an organization that tracks those trying to live longer by severely restricting their diets, gave up the effort himself. In his 30s, he found that lifestyle too tough to put up with for 60 to 70 years. Delaney now takes resveratrol.

Side benefits

Calorie cutting and resveratrol seem to have other benefits.

Two Harvard studies, published in 1997, concluded that being 15 to 20 percent underweight lowers the risk of death from all causes. Other credible research found that eating significantly less food lowers blood pressure, increases so-called “good” cholesterol, and lessens chances of dying from cancer, heart disease, and stroke.

Worms and rats put on severely restricted diets show a high rate of infertility, but those fed STACs don’t have that problem.

Resveratrol could also turn out to be an effective drug for preventing some cancers. The National Cancer Institute is testing it on people with a high risk of colon cancer. Two other STACs – quercetin and fisetin – have proven safe enough to be tested as anti-diabetes drugs.

Sinclair has started a company, called Sirtris Pharmaceuticals, to make a variety of synthetic STACs. The company hopes to start testing the drugs on diseases of aging, like diabetes, in a year or two. After that, it might be on aging itself. “At least, that’s what we’re hoping,” he says.

“We have something that extends the life of every species it’s given to,” Sinclair enthuses. “We’re 50 years ahead of where I thought we would be 10 years ago.”